« March 2007 | Main | May 2007 »

April 29, 2007

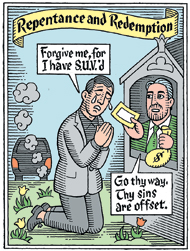

The New Church

As a follow up to my last post, the New York Times has a slightly different comparison of the environmental movement to the pre-Reformation church, together with this great little graphic:

Posted by David Mader at 02:27 PM | (0) | Back to Main

Bad Science

I decided in the early fall of last year to teach myself about global warming - not about the political debate but about the scientific theory. But the more I read, the more I discovered the difficulty of separating scientific theory from political debate. Almost every source, from my little Rough Guide to Climate Change to the theoretically authoritative Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, incorporated some degree of tacit assumption, and some summary dismissal of opposing points of view.

But nothing demonstrates the failure of the scientific method in the climate change debate better than this story out of England:

A group of British climate scientists is demanding changes to a skeptical documentary about global warming, saying there are grave errors in the program billed as a response to Al Gore's "An Inconvenient Truth."The crux of the enlightenment - and of the scientific revolution - was the rejection of arguments from authority. Truth was not what the Pope said it was; truth was what could be demonstrated and observed, repeatedly, by independent observers. The scientific method operates through the publication of theories and their submission to testing by others."The Great Global Warming Swindle" aired on British television in March and is coming out soon on DVD. It argues that man-made emissions have a marginal impact on the world's climate and warming can better be explained by changing patterns of solar activity.

An open letter sent Tuesday by 38 scientists, including the former heads of Britain's academy of sciences and Britain's weather office, called on producer Wag TV to remove what it called "major misrepresentations" from the film before the DVD release -- a demand its director said was tantamount to censorship.

Bob Ward, the former spokesman for the Royal Society, Britain's academy of science, and one of the letter's signatories, said director Mark Durkin made a "long catalog of fundamental and profound mistakes" -- including the claim that volcanoes produce more carbon dioxide than humans, and that the Earth's atmosphere was warmer during the Middle Ages than it is today.

"Free speech does not extend to misleading the public by making factually inaccurate statements," he said. "Somebody has to stand up for the public interest here."

Ward has also complained to Britain's media regulator, which said it was investigating the matter. British broadcast law demands impartiality on matters of major political and industrial controversy -- and penalties can be imposed for misrepresentations of fact.

But here we have a group of 'scientists,' led by a former head of Britain's ostensibly premier scientific organization, refusing to engage a theory they believe to be wrong. Science would suggest an open refutation of the claims in the documentary that they believe to be erroneous. Instead, these 'scientists' seem to be asking the government to prohibit the dissemination of an errant theory. This is not science.

Note the fundamental assumption of the 'scientists': that in an age of mass media, certain theories are too dangerous to be allowed to be disseminated to the public. The identification of those theories is left, apparently, not to the public - those poor, stupid souls - but to the scientific establishment. They have the authority to determine what is good science and what is bad; what is good science may be discussed, but what is bad science must be suppressed.

They have the authority. They are making arguments from authority. They are suppressing heresies. They are not scientists.

IF YOU WANT SCIENTIFIC METHOD: The Independent does the real legwork. Someone put them in charge of the Royal Academy. [Via David Akin]

Posted by David Mader at 12:11 PM | (2) | Back to Main

You Don't Come In Here and Piss on My Rug

"Former Vice-President Al Gore deserves acknowledgement for the success of his film in highlighting the huge ecological challenge of climate change.

"It is difficult to accept criticism from someone who preaches about climate change, but who never submitted the Kyoto Protocol to a vote in the United States Senate, who never did as much as Canada is now doing to fight climate change during eight years in office, and who has campaigned exclusively for hundreds of Democratic candidates who have weaker plans to fight greenhouse gases than Canada's New Government.

"We're going much farther than Al Gore went. He was the second most powerful man in the world and greenhouse gas emissions went up when he was vice-president.

"You know, it's easy when you've had the big job and then you're on the side lines -- it's easy to complain. My responsibility, our government's responsibility, is to act. If we came forward with our environmental plan in the United States, they'd call it revolutionary because it's so tough.

- Environment Minister John Baird

AS A SIDE NOTE: The best is the enemy of the good, and you have to wonder about the seriousness of folks like David Suzuki and Al Gore who preach the necessity of action on the environment but then denounce serious measures like the new Tory plan. It's true that the Tory plan wouldn't help Canada to meet its literal Kyoto obligations - there's no help for that now, since Kyoto obligations are paid up not in 2012 but from 2008 to 2012. And it's true that David Suzuki has indicated that he wants Canada to meet those obligations regardless of the patently disastrous economic costs. But even if he does want Canada to beggar herself on the altar of global warming, does it really make sense to speak out against the second-best Tory plan?

In other words, does David Suzuki seriously believe that the alternative to a Tory plan is a Kyoto-meeting plan? If so, it's time to stop listening to David Suzuki on matters political. Because there's no way even a (responsible) Liberal government would introduce a plan to meet Kyoto targets. A Dion government might - I have no reason to think Dion would be responsible on this front - but to institute such a plan would do more to guarantee a perpetual Tory majority than anything Stephen Harper could hope to do.

Let me put it like this: opponents of the Tory plan have repeatedly cited the Stern Report's claim that the longer we wait to act on global warming, the larger the hit to global GDP will be. They use it as a sword to attack the delayed target dates under the new plan. But if Stern is right, then why is it wrong to suggest that meeting Kyoto now is exponentially more costly than it would have been in 1997 or 1993?

The fact is that it's not wrong. The costing of the Dion plan that Baird announced before a Parliamentary committee a couple of weeks back was not a political costing or a Tory costing; it was a bureaucratic costing, seconded by impartial economists. Meeting our Kyoto targets is probably impossible at this point, and ballparking those targets would be economically disastrous - impacting far more lives in a far more negative way, I'd bet, than the hundred-year impact of global warming. The Tory plan will still be costly - very costly. I have to admit that taking such drastic action on the basis of what has quickly become a scientific orthodoxy - a paradox, incidentally, and an attack on the scientific method - troubles me. But it's clear that action on climate change is demanded. I have heard many arguments why the Tory plan does not do enough. I have yet to hear a compelling argument that what the Tory plan does is itself bad.

The best is the enemy of the good.

UPPERDATE: Paul Wells sees "incoherence" in Baird's criticism of Gore's failure to submit Kyoto to the Senate, when the Tories aren't submitting there own plan to the house. Some questions for Mr. Wells: 1) Did the Clinton administration have an administrative plan to implement Kyoto or some part of it? 2) Did the Clinton administration in fact carry out that plan? 3) Is the Tory promise to move forward through regulation rather than legislation a good faith promise? 4) If the Tories are indeed going to move ahead with their regulatory plan, while the Clinton administration failed even to move ahead regulatorily, then doesn't Baird have a point? I realize I'm splitting hairs, and Wells certainly has a rhetorical point, but I'm not sure the Baird position is fundamentally incoherent.

Posted by David Mader at 11:55 AM | (1) | Back to Main

April 25, 2007

The National Post on Afghan Torture

The Post has a strong editorial, arguing that Canada's continued presence in Afghanistan should be contingent on positive improvements in prisoner treatment by the Afghanis. Although I broadly agree with their assessment of the situation, I think it's as unhelpful to attach conditions to our continued presence as it is to attach a firm date to our removal. What that points to, of course, is the difficulty of achieving real reform on the part of the Afghanis, if hard demands like the Post's are in fact inappropriate. Either way, I do think it's fair to say that the issue has been mishandled by the Harper government. They were right not to roll over at the first Opposition fusillade, but they could have been more affirmatively responsive to the legitimate concern that underlay the criticism.

Posted by David Mader at 07:13 PM | (1) | Back to Main

April 24, 2007

Politics in Motion

Between this and this, I get the feeling the Liberals are in the process of being hosed, and I don't think they have any idea.

But I think they'll soon find out.

Posted by David Mader at 09:47 PM | (1) | Back to Main

A Question of Journalism

Isn't it good journalistic practice to have two sources for any story?

Look, allegations of abuse at the hands of Afghani security forces deserve serious and detailed investigation. But Stock Day isn't wrong to criticize the opposition - and the Globe, for that matter - for taking at face value the allegations of individuals detained by the Canadian army. Whether Canada ought to alter its practices prior to independent confirmation of torture allegations is, I think, a close question - at least as long as those allegations remain entirely mono-sourced. The opposition may be right that we should hold on to prisoners in the meantime; but deciding otherwise hardly seems a firing offense for the Defense Minister.

And this comes, remember, from a guy who thinks the Defense Minister should go.

IMMEDIATE UPDATE: On balance, I must say, I'm inclined to believe that abuse is occurring, even if I'm not inclined to believe, absent authentication, the allegations of individual detainees. That cuts in favor of not handing prisoners over to Afghani authorities. But that raises the question of how to proceed. Establishing Canadian-run detention facilities is far from ideal. On the contrary, the goal should be the establishment of professionally run Afghani facilities; after all, it's their country. But that suggests that we need to increase, not decrease, our presence in Afghanistan, in order to assist in the creation and sustenance of such domestically run institutions.

Posted by David Mader at 09:03 PM | (0) | Back to Main

A Good War

Good news out of Ottawa as an opposition motion to set a withdrawal date for our troops in Afghanistan was defeated, with the support of the New Democratic Party.

I have to say I'm perplexed by the evolution of the Liberal Party's Afghanistan policy under Stéphane Dion. The party has gone from a responsible position - advocating a larger humanitarian role for Canada in Afghanistan - to an irresponsible position - advocating the simple withdrawal of Canada's armed presence. The focus, in other words, has shifted from the conditions necessary for victory to the conditions sufficient for termination. Indeed, I suspect M. Dion wouldn't be able to state a coherent set of victory conditions; neither he nor his party seem interested in winning the war, only in ending it.

That's too bad. Canada is doing remarkable work in Afghanistan. I get a daily GoogleNews e-mail with stories about Canada in Afghanistan, and I recommend my readers sign up for a similar alert. Yes, Canada has suffered casualties; that's the cost of international responsibility. But our war dead have given their lives in one of the most honorable - and successful - foreign engagements Canada has, I think, ever been involved in. Kandahar province is quiet enough today that Canadian troops have been able to move to neighboring provinces to shore up other NATO contingents. That's a testament to the successes that our troops have had to date.

But the mission is not over. It's not over in Kandahar, where the rebuilding must continue - a rebuilding that the Liberals once supported, and that will require the continued presence and protection of Canadian troops. And it's not over in the country at large, which is fighting to sustain a nascent representative government against a set of tribal gangsters and foreign terrorists who see the young government as a creation of the non-Islamist west - and who therefore see the defeat of that young government as a victory over the non-Islamist west.

The Prime Minister and members of his caucus have suggested that the Liberals sympathize with our enemies in Afghanistan, and I think that sort of talk is unprincipled and inaccurate. I'd suggest to the contrary that the Liberals - at least under Dion's leadership - have stopped thinking seriously about Afghanistan as a conflict between Canada and its enemies. They appear to think about it instead only as a source of domestic political advantage.

Canada is doing tremendous work in Afghanistan, and that work has dividends that Canada will enjoy for years. It has dividends for the Canadian army, which is gaining valuable experience in combat situations. It has dividends for Canada's foreign policy clout, particularly within NATO, given the leading role we have played - and have been recognized as playing - in the Afghanistan campaign. And it has dividends for Canada as a leading member of the community of free nations, directly promoting, as we are, the freedom of Afghani men and women from the chaotic tyranny to which they would be condemned if we were to withdraw now.

War is hell. But on the terrible scale wars occupy, Afghanistan is a good war. It is a war worth fighting. The Liberals once thought so. It is a shame they've changed their minds.

Posted by David Mader at 08:04 PM | (1) | Back to Main

I Was Not Aware of That

Did you know that the tenth richest man in the world is a Canadian? And that he's properly styled Lord Thomson of Fleet? And that his company - Thomson Corporation - owns Westlaw? I did not know these things.

Here's my real question though: are the Thomsons Grits or Tories? Or, more particularly, do they - or have they - funded any think-tanks or other civil society organizations?

Posted by David Mader at 02:04 PM | (0) | Back to Main

April 23, 2007

Cool

Steven Landsburg, guest-blogging at the Volokh Conspiracy, has a neat post about patents. And yes, I've now used the terms 'cool' and 'neat' to refer to something about patents. I'm a geek.

Anyway, here's what he says:

The problem with patents is that they reward good behavior (that is, inventiveness) with a license for bad behavior (that is, monopoly pricing). It's rather like rewarding good samaritans with licenses to drive drunk. Surely there's a better way.The only thing I wonder is this: wouldn't bidders discount - or perhaps over-value - the price of the patent by the likelihood that the government would take it from them? In other words, if I know there's a 90% chance that I won't in fact receive the patent I'm bidding on - and therefore a 90% chance that I won't have to pay what I'm bidding - won't that distort my bidding activity?Kremer's proposal is essentially this: When you design a better mousetrap, we grant you a patent. The next day, the government purchases the patent for a fair market price and puts it in the public domain. The inventor gets his reward, and the rest of us get to buy goods at competitive prices. We pay through the tax system only what the inventor would have extracted from us anyway, and we get the additional benefits of competition: more mousetraps are built, and more inventors can start piggybacking on the idea.

The sticking point is determining that "fair market price". But Kremer has solved that problem: First we grant the patent. Then we auction the patent to the highest bidder. As soon as the auction ends, the man from the government arrives and flips a coin. If the coin comes up heads, the auction winner completes his purchase; if it comes up tails, the government buys the patent for the amount of the winning bid. Bidders have every incentive to bid judiciously because the coin sometimes comes up heads. But this way, half of all patents end up in the public domain, which is halfway toward solving the problem.

That's the naive version of the plan. In the sophisticated version, the man from the government flips a weighted coin, so that he wins 90% of the time. (You can't go all the way to 100% or bidders will have no incentive to perform their due diligence.)

The risk that I will have to pony up will dissuade over-valuation to a certain degree, of course - but since that risk is only (say) 10%, won't there be at least a certain degree of over-valuation? If that's the case, then the government can be expected to overpay by some fraction for each patent that it in fact purchases, and the patentee can be expected to be overpayed by the same fraction. Now perhaps this fraction is a worthwhile cost for public access to otherwise-monopolized inventions. But certainly it's a cost, right?

Posted by David Mader at 01:43 PM | (0) | Back to Main

Good News Out of Virginia Tech

Last week's shooting at Virginia Tech was an awful thing, but the increasing mania that marks the public response to the shooting has started to worry me. We're not nearly approaching a Diana-style response, but something about the ongoing focus - the flags down here in Austin, both government and private, remain at half-mast - is a bit troubling.

So I'm both pleased and relieved to see this bit of common-sense coming from the Virginia Tech students themselves. The Tech student government has asked the press to leave campus by Monday, when classes resume. A spokesman for the organization said that students felt that it was time to move forward, and that meant, in part, getting the campus back to normal.

Good for them. They've been through a lot this past week, and at least some seem to have emerged more mature than so many who claim to be offering sympathy.

Posted by David Mader at 12:01 AM | (0) | Back to Main

April 19, 2007

Rusty

I know I say this every time I come back from an absence, but I'm off my game - long, rambly, poorly constructed posts. It'll take some time, but I'll get it together.

Posted by David Mader at 12:47 PM | (0) | Back to Main

Apportioning Representation

Andrew Coyne has been taking some flak for his position on proportional representation. While I don't agree with Coyne, I think his position is a good one, and I think, frankly, that he has the better of the argument as it's gone so far.

My opposition to the sort of PR Coyne seems to be endorsing proceeds on different grounds. I don't think many of us would argue that representation in a democracy should be absolutely disproportionate; we all think that apportionment of representatives in an elected assembly should have some relationship to the apportionment of interests in the body politic.

But many of us would be equally uncomfortable with an absolutely proportional system - a total democracy. In a democracy, of course, the majority rules. But the very essence of a liberal democracy is its commitment to the guaranteed security of the liberties of each citizen, regardless of their membership in a political majority.

It all sounds very abstract, especially in a Canadian context. Let me put it in more concrete electoral terms. An absolute proportional system would give a majority of seats in the (proportionately elected chamber of the) legislature to the single largest coherent interest in the body politic. I'd suggest that in today's body politic, that means urban voters. I'm willing to be persuaded otherwise, but I think it's fair to say that urban voters have more in common with one another than they do as a group with rural voters. They also represent a greater proportion of the population than rural voters. So the consequence of a purely proportional system would be a solid majority in the house representing the interests of a majority of the electors, with those interests being urban interests rather than rural interests.

Some may not see this as problematic; after all, if a country is mostly urban it makes sense that the urban interest control. But there are a number of reasons why we might want to dampen this absolute proportional effect. The most compelling, to me, is that a national legislature ought to guard against the passions of a present majority. There are, again, a number of ways to do that. First past the post is one.

A first past the post system is still, it should be noted, a somewhat proportional system of apportionment. After all, as long as electoral districts are apportioned according to population - so that each riding has roughly the same number of electors - then urban areas will naturally have more representatives than rural areas. The dampening comes in not at apportionment but at the ballot box: each riding chooses its member with a certain number of votes, and the number of votes for that member (or party) beyond the number necessary to secure victory are counted merely as excess. In a pure PR system, of course, votes beyond those necessary to secure victory would still count; and if I'm right that urban areas are more likely to share interests (and vice versa in less populace rural areas), then the accumulation of those 'extra' votes would increase the representation of the urban interest. FPTP enhances the minority interest by discounting the intensity of the majority interest. It is, in other words, a compromise.

But it's not perfect, at least not as it currently exists. The problem is not with FPTP, though, but with where the post is put. Right now the post isn't put anywhere; it is set, once the votes are in, directly behind the vote tally of the winner of a plurality of votes. You 'pass the post' merely by winning more votes than anyone else, even if you don't win a majority of the votes cast. The fix is simple: set the post at 50%. If no one candidate won 50% a run-off would be required, but an instant run-off can be had through the use of a single transferable ballot, which reapportions votes according to second and (if necessary) third choice.

The result would be that every member would indeed enjoy the support of a majority of his or her constituents. But it would also maintain the hedge against excess majoritarianism that would reign under PR.

The criticism is that even under such a system, the votes of a number of groups "doesn't matter." If it only takes 50%+1 votes to win, and you're the 52nd majority voter, your vote is essentially worthless - goes the argument. And if you're among the 49% of minority voters, your vote "doesn't count at all" - whereas, under a pure PR system, it would contribute to minority representation in the house.

Only one of these is a fair criticism. The first - that members of the 'excess' majority are effectively disenfranchised - relies on two fallacies. It assumes that we can tell which voters are 'necessary' to constitute the bare majority, and which voters are 'excess.' But of course we can't; if you have a pool of 60% of majority-candidate voters, you can draw a circle around any 50%+1 of them to create the necessary majority; in other words, you can construct a majority in which they are the necessary voter. But we needn't even do that, which points to the second fallacy: the franchise is a right to vote, not a right to determine the very outcome of an election. The claim that excess votes don't matter is a claim that every voter has a right to be the +1 voter. But no voter has that right. The 52nd - or 78th - majority voter has contributed to the majority, and that's quite enough.

But what about the minority voter? Under a PR system, "every vote counts," in that it doesn't matter whether you're in the majority in your locale, since you'll still be represented in the national legislature (provided your interest meets some minimum national threshold). In a true FPTP system, however, a minority voter in a particular district has no immediate representation in the legislature, and is represented, if at all, only indirectly by like-minded representatives elected by like-minded majorities in other districts.

The truth is that the mixed PR system proposed in Ontario and discussed by Coyne does address this problem. By supplementing the FPTP-elected members of the legislature with a certain number of PR-elected members, the system incorporates the interests of local minorities without tilting the balance too much towards pure proportionalism.

Nevertheless I'm not in favor, because I think it's ultimately destructive of political discourse and activity. It encourages the notion that members of the political minority in an electoral district are not in fact represented by their elected representative if they disagree, politically, with that representative. But an MP is the MP for every voter in his riding, and has a duty to represent the interests of every voter in his riding - to the best of his abilities, and subject to his rather broad discretion where those interests conflict. What I fear is not polarization in the sense of partisan radicalism, but polarization in the sense of a disconnect between constituents and representatives, and a disconnect among constituents themselves.

I propose instead a theory whereby enfranchisement involves a right to participate in the election of a local representative and a right to campaign and persuade one's neighbors to elect a (different) representative with whose political views one agrees, but not necessarily a right to elect only a representative with whose political views one agrees. In other words, you don't always get to win. (As a Tory voter from Ottawa-Center, I speak from particular experience.) What you do get to do is take your best shot at winning at the ballot, and then work to persuade your neighbors prior to the next ballot.

That, I think, is much more productive of a healthy and engaged political discourse, rather than a retreat into ideological polarization. PR discourages political dialogue except to the degree absolutely necessary to win a working national majority, and - since an absolute majority is less likely - what we'd be more likely to see, I think, is the construction of coalitions of still-polarized groups. A coalition is certainly healthy, but recognize that it does not involve persuasion; it involves recognition of disagreement, which is terrific, but still second-best.

So don't give Coyne a hard time; he's not wrong. But there are at least a couple of reasons to argue that he's not 100% right either. PR, even in the modest form in which Coyne endorses it, has its costs - on the street, in the church hall, at the PTA, if not in the House - even while it has its benefits. There is a way to achieve at least some of its benefits without submitting to its costs. Single member single-transferable-ballot districts are the way to go. It's a better kind of democracy.

Posted by David Mader at 11:34 AM | (0) | Back to Main

April 18, 2007

Hold the Train

Stephane Dion can lead on climate change? Well hot damn - someone make this guy Prime Minister.

Honestly, though, you're finally fighting back against months of Tory spin, you recognize that the Tory spin has cast Dion as incapable of leadership, and yet you choose as your example of leadership an issue that has become a bit of a national joke where Dion is concerned?

Really?

AND ANOTHER THING: Dion is to be credited for focusing on himself rather than on the PM, something that the PM himself did to great effect in the 05/06 campaign. The more you talk about the PM, the more people think about the PM, and you want people thinking about you. But the goal is not to have people think about you; it's to have people think about you as prime minister.

And, believe it or not, an ad about Stephane Dion that focuses on his leadership abilities is not really about him being prime minister. In another context it might be. But for months the Tories have been spreading the notion that Dion is not a leader. Really - the message isn't much more sophisticated than that.

So what we have is the Tories saying "Stephane Dion is Not a Leader" and the Grits saying "Yes He Is." That's not a message about Stephane Dion as a leader; it's a message about the debate over whether or not Stephane Dion is a leader. It's not a debate that's going to be won by simple assertions in television commercials; it's a debate that's going to be won (or not) by, you know, leadership. You can lead in opposition; Harper did during the last campaign, and it worked. Dion needs to start doing that.

Twenty bucks says he won't.

Posted by David Mader at 03:47 PM | (2) | Back to Main

April 17, 2007

Debating Abortion

Fascinating column by Jonathan Kay in today's Post. Some thoughts:

- This isn't the first time that left-wing groups have tried to shut down debate on this matter on Canadian university campuses. This is a pure refusal to disagree. Beyond anything else, it's shameful. It shouldn't matter that this occurs on university campuses; free thought and free expression are universal in a democracy, not ghettoized at the academy

- Kay notes that the anti-intellectual activity at McMaster was spearheaded by a local chapter of the Canadian Union of Public Employees. Now I'm not saying that unions are always and everywhere engaged in thuggery, but it's remarkable how often we see or hear of examples of union thuggery in the news in Canada, isn't it? Thankfully that thuggery is not, for the most part, violent - although interfering with the freedom of movement and enjoyment of property rights is as deeply illiberal as any assault and battery. But though nonviolent, this anti-intellectual thuggery is as destructive of liberal government.

- One can't help but ask: why are Teaching Assistants at McMaster represented by the Canadian Union of Public Employees? They are, I suppose, public employees of a certain sort - although only on the theory that the university is a state actor. But if the school is a state actor, then its employees are state actors, and for its employees to restrict free expression on campus would represent a violation of Section 2 of the Charter.

- Putting the union issue to the side, Kay makes a strong argument for the public discussion of abortion, noting that Canada is "the only civilized nation in the world without an abortion law." He doesn't in fact make a strong argument for what that law should be; that wasn't his point. But the simple point that Canada needs some legal guideline on abortion is, I think, a fair one. You'd think we could at least enact the standard of Roe v. Wade.

- Kay lays blame in part at the feet of Conservative politicians who are too afraid of the small but vocal minority of pro-choice radicals. I think he's right. In a number of fields, Canadian political discourse is simply non-existent. That's bad for Canadian political culture, even - especially - for those who agree with the status quo. "Reason is by what is contrary," said Milton. As I've put it more verbosely: "Precisely because a moral conviction is based upon a belief as to a first principle, it's important that the conviction be subject to criticism in order for the holder of the conviction to determine whether that conviction is (or ought to be) truly held."

- Although I've blogged a number of posts relating (in some way) to abortion, I'm not sure I've ever posted my full argument for a libertarian opposition to late-term abortion. I think the time may be coming. For now I'll rest on a political slogan: Enact Roe v. Wade!

Posted by David Mader at 12:02 PM | (5) | Back to Main

April 16, 2007

Rap and Logical Reasoning

One of the top songs in the US since Christmas is Shawn Mims's "This is Why I'm Hot." (It appears not to have made it onto the Canadian charts.) When I first heard the song, I dismissed it as not particularly sophisticated or insightful. But after repeated hearings - it was on all the time - I realized that Mr. Mims had in fact given us a rather profound exposition of the difference between necessary and sufficient conditions.

The chorus of the song goes as follows:

This is why I'm hot; this is why I'm hot/Now that middle line - "I'm hot 'cause I'm fly; you ain't 'cause you not" - really stuck in my craw, until I realized how sophisticated it was. Mr. Mims establishes in the first two lines of his chorus that he's about to set forth the conditions of hotness.

This is why - this is why - this is why I'm hot/

I'm hot 'cause I'm fly; you ain't 'cause you not/

This is why - this is why - this is why I'm hot.

The first condition - I'm hot 'cause I'm fly - sets out a sufficient condition for hotness. If you're fly, you are hot. But on its own, this statement doesn't tell us whether being fly is the only way to be hot.

Mims answers the question with his next lyric: "you ain't 'cause you not." In other words, a simple deficiency in flyness precludes hotness. Being fly is not only sufficient to make one hot, it is in fact necessary. Because I am fly, I am therefore hot; because you are not fly, you are therefore not hot. Q.E.D.

See? This law degree is already paying off!

Posted by David Mader at 12:22 AM | (3) | Back to Main

Electing Judges

Calgary Grit notes a recent poll finding strong support among Canadians for the election of judges. CG finds the result "absolutely shocking considering what a dumb idea that is," and suggests that if Canadians "reflected on it for a bit, most would change their opinion quickly."

As it happens, I'm a Canadian, and I have reflected on it - for more than a bit, too - and, lo and behold, I have an opinion. So I thought I'd share it.

Off the bat let me say that I'm not in favor of elected judges, on balance. But it's not the outrageous idea so many think, and it's certainly not dumb. To see why, we have to spend a little bit of time considering the nature of law.

Most folks, asked to say who makes law, would identify Parliament or their local legislature. It's a good answer, and while it's not complete - law comes from an awful lot of places these days - it's close enough for government work. And most folks, when asked what a judge is supposed to do, would say something like "he's supposed to apply the law." And that's true, too.

The common law, which is the system of law that developed in England and which is still used in almost all of Canada, distinguishes between two parts of a case. There are questions of fact, which are evaluated and decided by the 'factfinder' - either a jury or a judge wearing his fact-finding hat; and these questions of fact, once decided, can't really be overturned on appeal. Then there are questions of law, which are evaluated and decided by the judge. Questions of law are basically the only questions which can be reviewed on appeal.

So the judge's job is indeed, like most folks would say, to apply the law. The problem is, that's not always easy to do.

It's not always easy to do because applying the law means understanding the law, and sometimes the law isn't entirely clear. Now, most of the time it is. Consider the law of theft:

(1) Every one commits theft who fraudulently and without colour of right takes ... anything, whether animate or inanimate, with intent (a) to deprive, temporarily or absolutely, the owner of it ... of the thing or of his property or interest in it.So if I take your bike, it's pretty clear that I've committed theft, and at trial the questions will all be questions of fact: did I really take it? When I took it, did I intend to deprive you of it? Are you really the owner of it? Did I in fact have some right or reason to take the bike? And so on.

Sometimes, though, the law isn't quite so clear. Here's how the Criminal Code defines criminal assault:

(1) A person commits an assault when (a) without the consent of another person, he applies force intentionally to that other person, directly or indirectly.What if I throw water in your face from my glass? What if I squirt you with a water gun? Are those applications of force? They both are, at least in a scientific sense. But is it clear from the statute that they're both criminal? The language of the law - the language of the statute - is at least somewhat unclear. In a common law system, this is where caselaw kicks in: the judge is able to look at other cases where the law of assault has been applied, and by comparing the facts of those cases to the facts of the case before him, he's able to make a judgment as to whether this does in fact constitute an assault. Those cases thereby turn an unclear phrase 'force' into a more precise legal standard. In the technical language of legal theory, the caselaw turns an 'indeterminate' statutory text into a 'determinate' statutory text.

But here's the rub: sometimes the law is not only unclear on its own terms, but lacks any history of interpretation that would make it more determinate. Consider the Charter. Most Canadians know that the Charter guarantees our fundamental rights & freedoms - like, in section 2(b), the freedom of expression. Fewer might be aware that the very first section of the Charter subjects our precious rights and freedoms to a caveat: those freedoms are "subject ... to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society." So here's the question: what's a free and democratic society?

Is France a free and democratic society? Whatever we think about France, it seems pretty free and pretty democratic. And in France it's illegal to wear religious insignia or clothing in a public school. Does that mean that Quebec is free to ban the hijab in its schools? Or consider the United States. A federal court in Washington, D.C. recently decided that the Constitution guarantees to each individual American the right to own and keep guns. Does that mean that the long-gun registry isn't justifiable in a "free and democratic society"?

Obviously the precise interpretation of "free and democratic" society is subjective - that is, there's no one clear answer to the question of whether a particular restriction on liberty is constitutional. This was illustrated clearly just last month, when our own Supreme Court, in the case R. v. Bryan, upheld a law banning the publication of federal election results in the Maritimes before the polls close in BC. The law had been challenged on the grounds that it restricted the freedom of expression. None of the justices denied that it did. But the bare majority of five justices held that the infringement on the freedom of speech guaranteed by s.2 of the Charter was justified under s.1 of the Charter because it served the principle of "informational equality."

Now you can scour the Charter all day long and you won't find the words "informational equality." The term nowhere appears in the Constitution Acts of 1867 and 1982. Nor does it appear in the Canada Elections Act, even though "informational equality" is, according to the Court's lead opinion, the "true objective" of that Act.

But the Court since 1982 has developed a standard to help it determine what is and is not justifiable in a "free and democratic society." The standard is essentially that a restriction is justifiable when it serves a "pressing and substantial" governmental objective and is proportional to that objective, in that it "rationally connected" to that objective.

As I hinted above, the Court was basically split on this question, with five justices finding that "informational equality" was a pressing and substantial governmental objective that justified the restriction of free speech, and four justices finding that it was not such a pressing and substantial objective, and that even if it was in the abstract, the particular law in question was too heavy-handed to be called proportional.

There's a reason the justices split on this question: there's no one right answer. Both arguments are legally sound. The conclusion the Court came to was entirely consistent with the law they were considering. But - and here's the rub - had the Court come to the opposite conclusion, that too would have been entirely consistent with the law they were considering. Because the law they were considering was indeterminate. It simply didn't answer the question.

When the law is indeterminate in this sense, a legal system can proceed in two ways. It can decide that since the law then in existence doesn't give a clear answer, and since judges aren't responsible for creating laws, a court confronting an indeterminate law should simply refuse to decide, at least until the legislature steps in to clear up the confusion by providing a clear answer in law. Or it can decide that since so much of the law is in some degree indeterminate - after all, language is always subject to a certain degree of interpretation - and since the job of judges is to, well, judge, a court confronting an indeterminate law should do the best it can to decide the case.

Of course if the law really is indeterminate - if there's more than one 'right' answer - then a judge who does his 'best' job to decide a case will invariably employ some sort of ideological or subjective standard in choosing between the possible answers. The division on the Court in Bryan essentially comes down to a disagreement over whether liberty or equality ought to prevail when the two values come into conflict. I don't mean to suggest that the justices in the majority have and will always favor equality at the margin, and that the justices in the minority have and will always favor liberty. I only mean that in this particular instance, since either one of the two available determinations would have been legitimate, the ultimate determination of the case involved - and must have involved - the exercise of ideological preferences.

So judges do politics. Not politics in the sense of parties and platforms and all the rest, but politics in the sense of exercising - in at least some small number of cases - an ideological preference for one among the available legitimate legal conclusions.

And if judges do politics - if the job of judging necessarily requires, in certain instances, the exercise of an ideological preference - why is it wrong to select judges at least in part according to their ideology? Let's be clear that any judge ought to be - must be - otherwise qualified to sit on the bench. Ideology is not and should never be an independently sufficient condition for becoming a judge. But given a pool of candidates all of whom are equally qualified to sit on the bench, what's wrong with preferring those with a preferred ideological outlook?

Just because judges 'do politics' in this limited way doesn't mean, of course, that they should do politics in the more traditional way - by running for office. It does mean at the least, I think, that there's nothing illegitimate in increasing the ideological nature of the judicial selection process, as the prime minister did earlier this year. You'll recall the brouhaha that came when the Tories increased the number of essentially political appointees to the committee that recommends judicial candidates. I did not read then, and I still have not seen, any allegation that either the new members of the committee or the candidates they were expected to prefer were otherwise unqualiifed for their respective roles. The objection, as best I can tell, was that the prime minister had introduced politics into the judicial selection process. As I've now argued at length, politics is, in a limited sense, a fundamental part of judging, so it seems perfectly appropriate that it be at least a limited part of the process of selecting judges. (As an aside, does anybody really believe that the other members of the committee have no ideological preferences of their own? Of course they do; it just happens that, as members of what is essentially the establishment, they have establishment-favorable ideological preferences.)

So what about elections? The fact is that the difference between an election and an ideologically-informed appointment is a difference in form, not in substance. Those who oppose the use of ideology in the selection of judges will naturally, I think, oppose the use of elections. But I've argued here that the use of ideology in judicial selection is appropriate. If there is an objection to judicial elections, it is not therefore that it involves politics in the ideological sense.

One fair objection is that elections require judges to engage in politics in the fundraising sense. Elections are expensive, and the necessity of standing for re-election may well take the judge away from his court. But my impression is that electoral fundraising is not a significant problem in Canada, perhaps in part because of restrictions on the amount that a candidate may spend.

Of course electioneering requires more than fundraising; it requires (or at least seems to require) promises. The operating assumption is that judges running for election will promise to resolve future cases in a particular way - and that voters will reward rather than punish them for such promises. I'm not convinced that this need be a problem. As I discussed above, the area in which a judge is able to exercise true unfettered discretion (in a way that is politically meaningful) is probably relatively limited. Within that area, of course, it seems entirely appropriate for a candidate for judicial office to indicate how he'd decide; that's the whole thrust of my argument up to this point. If there's more than one good definition of "free and democratic society," there's every reason to prefer a judge who will choose the meaning you'd choose, and so there's every reason for that judge to tell you which meaning he'd choose. But much of the law is in fact determinate - for the significant majority of questions, I'd wager, there is in fact a single clear (or at least legally better) answer. I've seen suggestions that elected judges would 'ignore the law' in order to win support among voters. But a judge can't simply 'ignore the law.' If the law is in fact determinate and the judge nevertheless comes to a contrary conclusion, he'll be reversed. Now judges get reversed now and then, but a judge who is repeatedly reversed will, I'd suggest, be punished either at the ballot box or in the legislature, which has (or certainly ought to have under an elected-bench system) the power of impeachment. It's possible, of course, that an elected trial judge who 'ignores the law' will be affirmed by an elected appeals court panel and an elected Supreme Court - but in that case I'd suggest that either a) the law is not really determinate or b) we have a bigger societal problem on our hands than the mere election of judges. Because if a trial judge, a panel of appellate judges, and a majority of Supreme Court justices all come to a decision that is contrary to a clearly determinate statement of the law, in statute or otherwise, that would indicate a pretty significant disconnect between the judicial and legislative branches of government (at the least).

All that being said, I don't in fact support the election of judges. Although many of the objections to the system (some of which I've discussed, many of which I haven't) could be addressed through relatively minor changes to our justice system, there's another way to incorporate ideology into the judicial selection process that wouldn't require the same structural change. In fact, incorporating an ideological component into the current judicial selection model - by, say, I don't know, increasing the number of political appointees to the judicial appointments committee - would introduce an appropriate amount of politics without introducing the problematic issues of electioneering.

But an elected judiciary is not as absurd as so many seem to think. On the contrary, it's a perfectly natural response to a perfectly logical realization: that the law doesn't answer every question; that justice therefore requires discretion; that discretion relies on subjectivity; and that in a democracy, questions of subjective policy are settled at the ballot box.

Posted by David Mader at 12:11 AM | (0) | Back to Main

April 15, 2007

Editing Mr. Dion

Time to Put Big Industry on a Carbon Diet

We live in a global context world where we cannot separate environmental and economic challenges the challenges of government from the crisis of climate change. [Editor's Note: Climate change is an environmental challenge.] This presents gives us with an opportunity: By acting now, we can encourage the development and deployment of make green energy technology a reality in Canada and secure our prosperity for the long term.

Just as Canada was outspending its fiscal capacity with repeated annual deficits in the 1980s and early 1990s, the vast majority of large industries, including our own, are dramatically over-polluting, dumping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere at a rate that is already producing irreversible ecological, social and economic damage.

For a decade prior to Jean Chretien's election in 1993, national overspending led to deep yearly deficits. Today the problem is not overspending but over-polluting. Many large industries, including our own, are dumping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere at a dangerous rate. And just as future Canadians bear the cost of spending deficits, so too will they bear the economic, social and economic costs of overpollution.

Jean Chretien eliminated the deficit, but it took some tough action. Canada must now take immediate the same sort of tough action to balance this environmental deficit. This means by setting absolute emission reduction targets and laying out a comprehensive plan to help industry meet them. ¶It is clear that Canada's business leaders want and need to be part of this solution.[ < --

-- > ]What they need is a plan that sets absolute reduction targets and creates the necessary tools to reach these objectives. They want to be given clear targets so they can figure out how to make their businesses environmentally friendly. They need the tools to help them make this difficult transition while staying competitive. ¶Recently, the Liberal party put forward such a plan.[ < --

-- >]Our proposal puts industry on a carbon budget and sets absolute national [E.N.: I should pretty well hope they're national.] greenhouse gas emission targets that meet our international obligations. It puts a price on carbon so industry can no longer treat our atmosphere as a free garbage dump. [E.N.: Last paragraph business was a partner; now it's an enemy. Choose.] This puts a price tag on industrial pollution, helping our industries to realize that burning carbon has a cost. It sets up an accountable and transparent mechanism to have industry invest in its own efforts to tangibly reduce pollution. [E.N.: Making something sound complicated doesn't necessarily make it sound impressive.] But our plan also rewards those industries that reduce their emissions.

It rewards early movers for their efforts to reduce greenhouse gases. It , and it ensures that new investments in green technologies are deployed in Canada.

And it creates opportunities for our businesses to participate in domestic and international emissions trading that rejects so-called "hot air credits." [E.N.: Terms of art, if not defined, merely confuse. For instance, do you mean that businesses can engage only in emissions trading that does not involve the trading of "hot air credits"? Or, as seems more likely, do you mean that the Liberal plan rejects the Conservative government's characterization of emissions credits as "hot air credits"? If you mean the latter, your sentence structure simply does not effectively convey that message.] Importantly, it allows our businesses to participate in the global market for emissions credits, giving them the flexibility they need to reduce their emissions while staying competitive in the global economy.

In short, our plan stimulates the investment to that will make Canada's economic future more sustainable while giving companies a wide variety of the market-based options they need to determine how they can meet their reduction targets as cost-effectively and efficiently as possible. It also ensures that companies have access to and can compete within the emerging global carbon market. [E.N.: This is one of the market-based mechanisms, and it has already been directly addressed.]

In a report last month, TD Bank economists noted the advantages of using a range of market-based policies, subsidies and domestic and international credit trading to curb greenhouse gases.[ < --

-- > ]The report notes that placing an appropriate price on excess carbon not only ensures that the polluter pays, it but also alters business practices to spur encourages innovation while reducing the need for further, more intrusive and costly environmental policies.

We can expect Prime Minister Stephen Harper and the Conservatives to continue arguing argue that capping greenhouse gas emissions is too expensive. [E.N.: If you use the title "Prime Minister," the reader thinks of Harper as Prime Minister. The point of this exercise is to make the reader think of you as the prime minister. Also, if the Tories haven't made an argument yet, then you're just putting words in their mouth. If you're going to do that, just do it; don't pussyfoot around the fact.]

They are also likely to claim that producing a regulatory framework is all that is needed to adequately address the problem. They say a simple regulatory framework will fix the emissions deficit.

However, But economists, including like Don Drummond of the TD Bank, note say that regulations alone are both economically and environmentally inefficient, as they don't encourage companies to reduce their emissions beyond the minimum threshold for compliance. [E.N.: The average reader has no idea how or why compliance with a regulatory framework is less efficient than compliance with a hard cap. (Do you?) Leave it at an allegation of inefficiency.]

This short-sighted approach also sets up a restrictive regime that raises costs by taking market-based options like carbon trading off the table. What's more, the restrictive Tory approach takes market-based options like carbon trading right off the table.

Many of Canada's our industrial leaders support meeting the Canada's absolute reduction targets under Kyoto demands.[ < --

-- > ] A For instance, a senior executive at Suncor recently told parliamentarians, for example, that his company did not "predict job losses or impact on the economy" because of meeting its Kyoto demands if Canada honored its Kyoto obligations.

As well, And reports have noted say that Canada's oil and gas sector could increase profits by up to $1 billion a year while still decreasing emissions by 29 megatonnes per year, simply by investing in efficiencies and plugging leaks more efficient technologies.

The number of major corporations urging governments to implement caps on emissions tied to global warming continues to grow while the Harper government continues its irresponsible delaying tactics. The truth is that more and more companies are urging the government to implement caps on greenhouse gases, and all the while the Harper government only continues to stall.

Because greenhouse gases accumulate and remain in our atmosphere for decades, we must chart an aggressive course of action now to get Canada's economy on a low carbon track. Greenhouse gases accumulate in our atmosphere; once they're there, they're there for decades. That means we have to act now to stop our factories from polluting our children's air.

As British economist Nicholas Stern's recent report estimated, taking global action now would cost approximately 1 per cent of the world's gross domestic product, but delaying action for more than 20 years would cause a 20 per cent rise "each year, now and forever." [E.N.: A twenty percent rise of what? Temperature? Cost? GDP?] The British government's recent Stern Report suggested that taking the necessary action on global warming today would only cost one percent of the world's GDP. But it said that the longer we wait, the more it will cost.

So while some economists may caution that the short-term economic costs of taking immediate action on climate are too steep, these opinions must be balanced with the multitude of economic, social and human costs to the changes we are already witnessing due to the Earth's warming coupled with the increasing costs of inaction. Some say that taking action on climate change will be expensive, and they're right. But the costs of taking action now don't begin to compare with the costs of inaction.

Canada must act aggressively to avert the destructive consequences of climate change and be a part of the solution.

By driving this change and rising to the challenge of our generation, Canada will not only be acting responsibly, it will also set a course to become the green energy superpower this nation can be.

That means it's time to act. A decade ago, Jean Chretien made the difficult choice to cut the budget and get the country's finances in order. The challenge we face in global warming requires the same sort of resolve. This is the challenge of our generation. By taking strong action on climate change, by committing ourselves to serious targets, by taking the lead in this global campaign, Canada can make a real difference, and take its place as a green energy superpower.

Stéphane Dion is leader of the federal Liberal party

David Mader is not.

Posted by David Mader at 05:20 PM | (0) | Back to Main

April 12, 2007

Belinda

As a footnote to this footnote in Canadian political history, it's interesting to consider the paradox that Ms Stronach's brief public career presents. For if she was indeed the strong, capable woman that her supporters suggest, then she was perhaps the least competent electoral politician in recent memory; but if she was simply the victim of "spectacularly bad advice," as Andrew Coyne charitably puts it, then she can hardly be said to have been a particularly strong, capable woman.

Posted by David Mader at 09:38 AM | (1) | Back to Main