« October 2006 | Main | December 2006 »

November 28, 2006

My Bad

Why did I think PVL was Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Foreign Affairs? Keep up the good work, Deepak!

UPDATE: Turns out I thought PVL was Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Foreign affairs because PVL was Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Foreign Affairs. Oh, me of little faith.

Posted by David Mader at 11:20 PM | (0) | Back to Main

A Question for Daifallah

I hope my friend AD won't mind my calling him out like this, but I think this could be interesting. Adam was involved in a very interesting debate with, among others, Andrew Coyne, regarding the deux nations resolution. In response to the arguments by Coyne and Tom Axworthy regarding liberal political theory, Daifallah essentially argued (and he'll correct me, I hope, if I mischaracterize him) that theories were essentially irrelevant in the face of 'the facts on the ground' and 'the reality' of Quebec nationhood.

My question to Adam is where - or whether - he locates a limit to that principle. The notion of equality before the law is probably demonstrably or empirically disprovable based on, for instance, disparities in the incarceration rates of natives and whites. Should we forget about the notion of equality before the law? The principle of free speech was challenged by those who felt personal injury in the publication of the Mohammed cartoons. Should we restrict the principle of freedom of speech? Should we do so if those who are aggrieved create a 'reality on the ground' of violent response to free expression they deem unacceptable?

On a deeper level, what principle governs our recognition of 'the facts on the ground'? The great strength of liberal political theory is its objectivity - it restricts the number of normative judgments involved in the creation and perpetuation of a political state to essentially two: individuals ought to be free and they ought to be equal. But what objective or falsifiable principle will tell us exactly what the 'facts on the ground' are at any given time? In fact, isn't a 'facts on the ground' approach simply a warrant to impose whatever subjective political preference happens to enjoy majority support?

As I've said before, I know very little about Canadian constitutional issues, and I certainly defer to Adam regarding the state of affairs in Quebec. But rather than simply being more persuaded by Coyne's arguments in favor of one-nationhood, I'm actually affirmatively dissuaded by Adam's arguments in favor of dual-nationhood, at least insofar as those arguments rely on a preference for "facts on the ground" over classical liberal political theory.

As always, though, I'm willing to be persuaded. Reader thoughts are, of course, more than welcome.

FOR INSTANCE: Do these results constitute "facts on the ground"?

Canadians overwhelmingly rejected the concept of Quebec nationhood in a new poll released Tuesday, one day after all parties in Parliament declared the Quebecois a nation within Canada.And if so, why should the "facts on the ground" inside of Quebec - which, it turns out, are only "facts on the ground" as pertains to francaphone Quebeckers, thereby pretty clearly undermining the assertion that nationhood is non-ethnic - why should these "facts on the ground" trump the apparent "facts on the ground" in the other nine provinces of confederation? Why, that is, except for a subjective elevation of the interests and opinions of a sub-set of Quebeckers over the apparent states interest and opinion of a clear majority of all Canadians?Outside Quebec, 77 per cent of Canadians rejected the idea the province forms a nation, suggested the Leger Marketing survey conducted for the TVA television network and distributed to The Canadian Press.

Among regional, linguistic and Liberal party breakdowns, French-speaking Quebeckers, at 71 per cent, were the only group to “personally consider that Quebeckers form a nation.”

The exact question in the Nov. 16-26 poll was, “Currently, there is a political debate on recognizing Quebec as a nation. Do you personally consider that Quebeckers form a nation or not?”

Canadians from every region outside Quebec, non-francophone Quebeckers (62 per cent), Liberal party supporters (72 per cent), francophone Canadians outside Quebec (77 per cent) all resoundingly rejected the idea.

Posted by David Mader at 09:35 PM | (4) | Back to Main

Refusal-to-Disagree Watch

Sigh:

Sparks flew during question period at a Nov. 21 Carleton University Students’ Association (CUSA) council meeting after a motion that would prevent pro-life groups from assembling on CUSA space was tabled.The emphasis is mine, and it highlights the crux of the issue: certain students were upset that debate was occurring. This is not just a classic example of a lack of intellectual curiosity, it's a self-conscious embrace of same, combined with a self-conscious attempt to bully and coerce the intellectually curious into silence.The motion — moved by Katy McIntyre, CUSA vice-president (student services), on behalf of the Womyn’s Centre — would amend the campus discrimination policy to state that “no CUSA resources, space, recognition or funding be allocated for anti-choice purposes.”

The motion was met with resistance from Carleton University Lifeline, a pro-life student organization that was denied CUSA club status at an Oct. 26 council meeting.

According to McIntyre, anti-choice groups are gender-discriminatory and violate CUSA’s safe space practices.

The motion focuses on anti-choice groups because they aim to abolish freedom of choice by criminalizing abortion. McIntyre said this discriminates against women, and that it violates the Canadian Constitution by removing a woman’s right to “life, liberty and security” of person. . . .

McIntyre said she received complaints after Lifeline organized an academic debate on whether or not elective abortion should be made illegal.

“[These women] were upset the debate was happening on campus in a space that they thought they were safe and protected, and that respected their rights and freedoms,” said McIntyre.

Although my earlier post doesn't address the issue, it seems to me that there must be some limit on what positions are entitled to respect within a democratic framework. Although I'm still thinking the issue through, my tentative suggestion is that the only positions that ought to be placed beyond political conversation are those that enable the continued existence of the democratic political structure. In other words, free speech must be in some sense inviolable, because without a right to free speech no political discussion is possible. (That doesn't mean, of course, that there can be no debate as to the proper scope of free speech protections, only that some free speech protection must be put beyond political debate. I hope to explore the precise contours of this theory, and the other principles that ought, pursuant to the theory, to be placed beyond political discussion, in a later post.)

For now that brief outline suffices to allow us to consider the proposal to ban "anti-choice" opinions from Carleton campus. Notwithstanding the obvious lack of intellectual curiosity, the position might be justifiable if the underlying principle - the right to elective abortion - is considered fundamental to the continued viability of political dialogue.

It seems pretty clear to me that the total protection of an abortion right is not fundamental to the existence of political dialogue. Restricting abortion may well impinge upon certain of a woman's rights of personal and sexual autonomy, but I cannot see how it can be said to do so in a way that a) substantially limits a woman's ability to engage in political dialogue or b) undermines political dialogue in the aggregate.

A couple of notes: first, I'd argue that interference with the ability to engage in political dialogue requires an immediate and affirmative act by the state, and not simply a refusal to create (or even permit) conditions that would remove a non-state-created impediment to participation. In other words, you don't have a right to be published in the Globe & Mail. Second, I'd argue that it's the impact on the individual's ability to participate, and not on the effect of a restriction in the aggregate, that should inform our approach to the acceptability or otherwise of a particular policy when measured against the standard of "interference with the viability of political dialogue." But some might prefer an aggregate or group-right approach, and I'm not convinced that such an approach doesn't have some value. I'll have to think about it some more.

Note that under my approach it doesn't necessarily matter whether or not a majority of Canadians favor some restrictions on elective abortion - a fact that would establish controversy and so satisfy a standard that would put beyond political debate only those principles that were not subject to widespread controversy. If restricting abortion really did threaten the democratic political process, the mere fact that it was supported by a majority would not make it legitimate - the same way a majority's desire to suppress the speech of a minority does not make it legitimate.

And none of this, of course, goes to a) the absurdity of restriction freedom of speech and ideological diversity on a university campus, or b) the constitutional and legal claims of the 'womyn's' group. If the claim as to the fundamental nature of an unrestricted abortion right was correct, there might be a colorable claim as to the propriety of excluding contrary views even from a university campus (though there would be, in my view, stronger arguments against such an exclusion); and if the claim was correct, the law, to the degree that it differed, might be thought incorrect. But I think it's pretty clear that an unrestricted right to elective abortion is not, or at least ought not to be, one of those fundamental principles the questioning of which threatens the continued viability of a democratic political system. That being the case, refusal to allow discussion of the principle, let alone to engage it in argument, represents nothing more than the worst sort of close-minded lack of intellectual curiosity. These students should be ashamed.

[Via Volokh]

Posted by David Mader at 05:14 PM | (1) | Back to Main

November 27, 2006

The Question on Everyone's Lips

Who will replace PVL as Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Foreign Affairs?

Can we have a true believer this time?

Posted by David Mader at 10:25 PM | (0) | Back to Main

Status Quo

A brief comparison of the 2006 General Election and 2006 By-Election results in London North Centre and Repentigny:

London North Center - General Election

Liberal: 40.1%

Conservative: 29.9%

New Democrat: 23.8%

Green: 5.5%

London North Center - By-Election

Liberal: 34.9% (-5.2%)

Conservative: 24.4% (-5.5%)

New Democrat: 14.1% (-9.7%)

Green: 25.9% (+20.4%)

Repentigny - General Election

Bloc Quebecois: 62.4%

Conservative: 18.1%

Liberal: 8.7%

New Democrat: 7.7%

Repentigny - By-Election

Bloc Quebecois: 66.3% (+3.9%)

Conservative: 18.7% (+0.6%)

Liberal: 6.2% (-2.5%)

New Democrat: 7.0% (-0.7%)

In other words, the Tories and Grits both bled about the same amount of support to the Greens in London - and neither bled as much as the NDP. It's unclear how much of this can be attributed to the fact that the Green candidate was party leader Elizabeth May. But as between the Tories and the Grits, London voters appear not to have altered their views very much since January.

Similarly, the state of affairs in Repentigny appears essentially unchanged - and to the degree that voter preferences have shifted, they've shifted at the expense of the Grits - who finished fourth tonight behind the NDP, whom they'd beaten in January. The Tories saw an immaterial gain.

Point being, those who hoped to see in these by-elections a referendum on the Conservative minority will have little to play with. Whether these results - essentially an endorsement of the status quo - would be repeated across the country is another question. But it's a question the Grits would do well to ponder before plunging the country into another election campaign.

Posted by David Mader at 10:04 PM | (1) | Back to Main

Two and a Half Cheers for Michael Chong

This, my friends, is Parliamentary politics. As Garth Turner appears fundamentally incapable of understanding, there is a difference between a government and a majority (or, in this case, plurality) caucus. A Parliamentary party is a collection of MPs who, on balance, support a common platform. A government is a ministry; it is a body of MPs who advise the executive as to the administration of the nation (ahem). It is necessary that all members of a government vote in for that government; it would be inconsistent for a member of the government to vote against the government of which he or she was a member. When a conflict of principles arises - as really ought to arise far more frequently than it appears to - the appropriate action for a minister is to resign from government and withdraw to the back benches. There is no shame in such an action; on the contrary, it is the very height of Parliamentarianism.

So two and a half cheers for Michael Chong, a man even most politically aware Canadians had not heard of a week ago, for standing on principle and resigning his seat in Cabinet. One cheer is for his substantive position, with which I happen to agree; a second, more important cheer is for his willingness to act as a Parliamentarian should, and to forgo the perks of governmental office.

But I can't join the Post in endorsing a full third cheer, because Chong, despite his clear opposition to tonight's motion, failed to vote against it. He is reported as having resigned from Cabinet in order that he might abstain in the vote. But why abstain? I fear party 'discipline' was brought to bear in order to prevent him from too far crossing the party line. If that's the case, it's perhaps unfair to withhold the final cheer. But Chong could have struck a blow against overbearing parties as well as dual-nationhood tonight by voting against the Prime Minister's motion even as he continued to support the Prime Minister's ministry. There's no inconsistency in having a Tory MP vote against a resolution of the Conservative ministry. On the contrary, it's to be expected. After all, as I say, a Parliamentary party is a collection of MPs who, on balance, support a common platform.

The key is balance.

Posted by David Mader at 09:38 PM | (2) | Back to Main

One Nation: Short Version

Either it doesn't mean anything, in which case it's an inappropriate use of the legislature's time and a mischievous exercise of Parliamentary authority; or it does mean something, in which case it undermines the notion of an equal confederation.

Because I believe in an equal confederation - a confederation of equal provinces and of citizens equal before the law - I oppose tonight's resolution.

UPDATE (23:00 CST): Let me refine this a bit in response to Stern's comment.

First, let's put to one side the question of provincial equality and the nature of confederation. Canadian history is among the subjects that I'm in the process of teaching myself, but my early observations suggest that there's no clear consensus on this question. At the very least, Andrew Coyne appears to argue quite strongly that confederation was not, in fact, a coming together of deux nations. In any case, though, tonight's resolution clearly speaks of les quebecois et quebecoises, whomever they may be, thereby explicitly addressing people rather than political jurisdictions.

That being the case, let's revisit my two alternatives, but in reverse order. If this resolution has any meaning - if it has any legal or political consequence - then it must, necessarily, abrogate any notion of equality of citizens before the law. After all, the "it" in the question "does it have meaning" is the explicit recognition, by the legislature, of the particular status of a sub-set of all Canadians. Many proponents of the resolution appear comfortable with a future recognition of a laundry list of other nations within a united Canada - First Nations, Chinese-Canadians, Albertans, and so on. But this resolution does not recognize those purported nations. It does not even recognize a Canadian nation. Among all the possible nations within the dominion of Canada, it recognizes only one: les quebecois et quebecoises.

The resolution, if it has any meaning, thereby affords particular status to one subset of Canadians. That seems to me a pretty clear violation of the political principle of equality of citizens before the law - a principle that is enshrined in our Charter of Rights and Freedoms:

Every individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination and, in particular, without discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability.Emphasis added. Now I know nothing about Canadian constitutional jurisprudence, and I don't mean to suggest that tonight's resolution, if it has any meaning, violates Section 15(1) of the Charter by discriminating on the basis of national origin (which must, after all, be the very point of the motion if it has any meaning, right?), though I can't help but think that there's a colorable argument to be made along those lines. But I do think that the explicit recognition of one "nation" within Canada, without a concurrent and coextensive recognition of all "nations" within Canada as well as of a single Canadian national identity, violates the political principle of equality before the law - at least insofar as that recognition has any meaning.

But perhaps the resolution has no meaning, either legal or political; perhaps it does not constitute discrimination on the basis of national origin, despite appearing to recognize the particular status of one national group among all the national groups that claim existence within the political boundaries of the dominion of Canada. If that's the case, what's the problem with a little empty symbolism?

Well, aside from my previously stated objection that the time and energy of our national legislature and Her Majesty's government shouldn't be occupied in the pursuit of empty symbolism, I'd argue that even a purely symbolic recognition of dual nationhood is destructive of national unity.

The very nature of dual nationhood is exclusionary: there are particular groups within the body politic, and you're either a member of one or the other, but not both. Some Canadians are members of the "nation" of les quebecois et quebecoises. Some are not. It's unclear to me whether one who is not a quebecois can become a quebecois, and if Lawrence Cannon is the authority on the matter the answer would appear to be non. But even if membership in the two groups (which are, tonight, les quebecois et quebecoises on the one hand, and those who are not les quebecois et quebecoises on the other) were fluid, yet still the designations would be exclusionary: at any given time, some Canadians would be quebecois, and some would not.

Why should this matter? Well, it will matter inasmuch as the national polity relies on a notion of common interest or common weal in order to sustain its legitimacy and effectiveness. Dual nationalism by definition establishes areas of divergent interest, areas in which the common weal by definition does not exist and cannot be cited as a foundation for national governmental legitimacy. That's not to say that there will be no areas of common interest; on the contrary, presumably les quebecois et quebecoises and non-quebecois will generally, perhaps overwhelmingly, share common aims and common interests. (By interest I mean not political interest in the sense of political preference, but fundamental interest in the sense of the fundamental values that inform a body politic.) But if the deux nations shared every interest, then there would be no need to recognize any difference; indeed, the recognition of any difference would be illogical. We would all be quebecois. But if les quebecois et quebecoises are anything less than the entirety of the Canadian population, it stands to reason that they share in common certain fundamental interests that are not shared in common with the non-quebecois.

Supporters of dual nationhood cite language and culture. But it is one thing to recognize that a subset of Canadians share a minority language and a distinct culture; it is another to assert that these attributes inform a fundamentally different set of basic interests - that those who share a minority language and a particular distinct culture necessarily stand outside of the common weal, even if only as to those particular distinguishing attributes.

A subset of Canadians speak French and exhibit a particular culture? Well, bully for them. Some French-speaking culturally distinct Canadians will attach political importance to their language and culture - but they're entirely able to express their political preferences as full-fledged members of the Canadian national polity. What is achieved by removing these Canadians from the national polity, by defining them, indeed, so that they necessarily exist outside of it, except the division of the national polity into two camps? And having divided the national polity into two camps, how can we say that we have advanced, rather than undermined, the cause of national unity?

That's why I believe that even a meaningless resolution by the House is detrimental to national unity - provided we insist on a plain language meaning of the phrase "national unity." Dual nationalism necessarily rends the national body politic into two separate groups; having so rent the body politic, can the political institutions through which sovereignty is exercised really be expected to remain united?

(I guess this isn't the short version any more.)

Posted by David Mader at 09:35 PM | (2) | Back to Main

November 17, 2006

Red China

So let me run through this story - correct me if I get the dates wrong:

Tuesday: Chinese appear to call off any possibility of a meeting between Harper and Hu. Press surmises that the Chinese 'snub' was a reaction to the Harper government's strong pro-democracy stance in Asian affairs, particularly with regard to Taiwan and Tibet. Talking heads suggest that Harper is playing too much politics with China, thereby putting Canada's foreign trade interests at risk.

Wednesday: Harper shrugs off the snub, saying that while trade with China is important, human rights are more important.

Today: Chinese announce that Hu and Harper will meet after all.

Ok? Ok. Now:

1) How is this anything but a political victory for the Harper Conservatives? The Grits said (and seem now to say) that human rights rhetoric must be restrained, lest our trading relationship with China be compromised. The Tories say that unrestrained rhetoric is valuable in its own right. Harper speaks unrestrained rhetoric, and the expected consequence - the consequence the mere hint of which sent the press and the opposition into a tizzy - didn't pan out. As between the Grits and the Tories, who appears to be right?

2) Indeed, how is this anything but a diplomatic victory for the Canadian government? The Chinese said (publicly), "Because you criticize us over human rights we're not going to meet." Harper said (publicly), "Okay." The Chinese said (publicly), "Well, fine, we'll meet with you after all." As between Harper and Hu, who's shifted more from his initial position?

3) Of-freaking-course you can criticize China while maintaining a healthy trade relationship with them. These guys aren't babies - they understand the game, and they can take the heat. In any case, the Americans do it all the time. It's true that compared to the U.S. we're small potatoes - but that only makes it less likely that criticism will have negative consequences. If the Chinese ultimately don't care whether the Canadian government criticizes their human rights record - at least not enough to seriously hobble our trade relationship - we might as well go ahead and criticize them, right? I mean, we all agree about the substance of the criticism, right?

Right?

4) Unless the Chinese do actually care about Canada's public stance. But why might that be? We're too small a consumer market for them to care about, I think; I'd be interested to see numbers on the volume of natural-resource trade that heads west across the Pacific. But if it's not economic, what does that leave? Is it possible that, Conservative doubt aside, Canada in fact does retain a respected position in global politics? Is it possible that the Chinese would be more concerned about Canadian criticism than American criticism - since American criticism may be discounted in most of the world, but Canadian criticism will be seen as the product of a disinterested and trusted third party? And if that's the case, isn't it possible that it would be worth it to sacrifice our trade relationship with China in order to encourage the spread of human-rights-based criticisms across the globe? Because we all agree about the substance of those criticisms, right?

Right?

Olaf presents a contrary view here. Oh, and yes, one meeting does not a bilateral relationship make. Oh, and also, sorry about all the italics. I get carried away.

HOLD-THE-TRAIN UPDATE: I'm sorry, did renowned international human rights scholar Michale Ignatieff call Red China "one of the greatest civilizations on earth"? Ah, you say, but China is, after all, one of the greatest civilizations on earth. Well, China, yes; Red China, no. And it's quite obvious from the context of Iggy's quote that he's talking about the Chinese government, not about the Chinese civilization. Is Ignatieff intentionally equating Chinese civilization with Chinese communism? Does he think that the long march of Chinese history leads inevitably to communism? Does he think Chinese civilization could exist under some other, less tyrannical form of government? Does he think that Chinese civilization should exist under some other, less tyrannical form of government?

Just asking.

WE'RE-ALL-ORIENTALISTS-NOW UPDATE: "[Former Liberal foreign minister John] Manley urged the prime minister to 'read something about oriental culture and diplomacy.'" If he swatted up, presumably, he'd understand that tyranny is a cultural thing over there.

Posted by David Mader at 12:19 AM | (4) | Back to Main

November 14, 2006

National/Federal

I should probably wait until the full column is published, but I'm going to go ahead and note my one source of discomfort with regard to Andrew Coyne's 'le Canada est un nation' campaign. Coyne writes:

[I]t implies a direct relationship between those citizens, individually and collectively, and the one government that answers to them all: the national -- or if you prefer, federal -- government. That’s critical. Federalism, as such, is impossible without it.My problem is this: as political notions, nationalism and federalism aren't interchangeable. Ask these guys. Nationalism implies that the interests of all Canadians are best - and most appropriately - served by a single national government, and that provinces are merely administrative units of that central government. Federalism implies that while Canadians share a common national identity, their diverse interests are better served by a series of sub-national governments better suited to respond to the wide variety of concerns which Canada's tremendous size and diverse population encourages. If nationalism implies a single government with administrative sub-units, federalism implies a union of provincial governments.

Coyne would doubtless argue that, as an historical matter, the provinces are simply administrative units of the central government. I think he's probably right on that front. But given his commitment to classical liberal notions of government, I think it's important that the consequences of the choice between nationalism and federalism be more closely considered. (I don't mean to suggest, of course, that he hasn't considered them, as I've no doubt he has. I mean generally.) A nationalist would have a far different prescription for senate reform, for instance, than a federalist.

The point is that while we certainly cannot escape our history - and nor should we want to - it's probably useful for those of us who favor limited government to explore the ways in which the principles of federalism can be advanced under the Canada Act. Nor need federalism necessarily endorse separatism, although I must confess that I find the most prominent argument against the severability of a political union to be unpersuasive. Surely there must be a middle ground wherein the ends of federalism are achieved, consistent with our history, without resulting in the break-up of our country.

AS AN ASIDE: Anybody else think Coyne should be writing a book? He certainly seems to be among the most ardent champions of the single-nation theory. A pamphlet, even?

Posted by David Mader at 09:06 PM | (7) | Back to Main

Dear Garth

You're not that special.

Best, Mader

Posted by David Mader at 09:05 PM | (0) | Back to Main

Ottawa Mayoral Election Results

Anyone know where I can get my hands on a ward-by-ward breakdown of the Ottawa mayoral election results? The City - and various news outlets - have the unofficial citywide tally, which is all well and good for voters but doesn't do much for the political junkies among us. Ideas?

TO CLARIFY: I'm specifically looking for the ward by ward breakdown of the mayoral election; in other words, I'm looking for the number of votes that each mayoral candidate (or at least the top three - O'Brien, Munter, Chiarelli) won in each individual ward.

Posted by David Mader at 08:34 PM | (3) | Back to Main

November 13, 2006

Ideas Matter

And language is the tool by which ideas are transmitted. If it all sounds Orwellian, well, it is - in a sense. But primarily in the sense that Orwell understood, and documented, the connection between language and political ideas.

In any case, it goes without saying that the Liberal use of "catchphrases" identified in this article represented precisely the same sort of Orwellian branding and idea-transmitting. The Tories can only be expected to do the same. The focus should not be on the language used, but on the ideas meant to be expressed.

Posted by David Mader at 06:31 PM | (6) | Back to Main

Rudy '08

Very good news. Republicans would be mad not to put him somewhere on the ticket.

Posted by David Mader at 05:38 PM | (1) | Back to Main

Red China

To be perfectly honest, I think our relations with Red China should be a bit rocky. I don't think we should put affirmative obstacles in the way of trade, but I also don't think we should be bending over backwards to appease the world's largest tyranny. A constant, gentle reminder from Canada that China isn't quite there yet is a healthy thing, I think.

Posted by David Mader at 05:35 PM | (0) | Back to Main

November 12, 2006

Quote of the Day

Whatever it started out as, Iraq is a test of American seriousness. And, if the Great Satan can't win in Vietnam or Iraq, where can it win? That's how China, Russia, Iran, North Korea, Sudan, Venezuela and a whole lot of others look at it. "These Colors Don't Run" is a fine T-shirt slogan, but in reality these colors have spent 40 years running from the jungles of Southeast Asia, the helicopters in the Persian desert, the streets of Mogadishu. ... To add the sands of Mesopotamia to the list will be an act of weakness from which America will never recover.Have lots of kids and teach them to shoot. I'm not kidding.

Posted by David Mader at 04:44 PM | (7) | Back to Main

November 11, 2006

Unprecedented?

Can anyone tell me of a prior instance in which members of an opposition party have attended an international conference in order to deny that the government of Canada speaks for the people of Canada? Let's leave political philosophy - the fact that the government speaks for the people until it is defeated - out of it. Have opposition parties historically adhered to the notion that politics stops at the water's edge?

I SHOULD NOTE that I actually am interested to know if there have been prior instances; the tone of the post may have suggested that I thought none exist.

Posted by David Mader at 06:41 PM | (0) | Back to Main

In Flanders Fields

The poppies blow between the crosses,

row on row, which mark our place;

and in the sky the larks, still bravely singing, fly-

scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead.

Short days ago we lived, felt dawn,

saw sunset glow, loved, and were loved,

and now we lie In Flanders Fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe.

Take up our quarrel with the foe!

to you from failing hands we throw the torch;

be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die we shall not sleep,

though poppies grow In Flanders fields.

Posted by David Mader at 12:00 PM | (0) | Back to Main

November 10, 2006

Too Old

As anticipated by Adam, John McCain has begun his run for the White House in 2008.

In 2008, John McCain will be seventy-two. If successful he would be the oldest man ever elected to the presidency. In 2012 - when he would come up for reelection - McCain would be 76. He would leave office, if reelected, at eighty.

Now I have nothing against old presidents in the abstract. But keep this in mind: John McCain isn't a baby boomer. John McCain is older than the baby boom. There may, in fact, be something slightly comforting about baby boomers expressing dissatisfaction with their generation's presidents and running back to an earlier generation for guidance and leadership.

But, as I've said before, optics is often the key to politics. Imagine a 72-year-old John McCain on stage at a presidential debate two years from now. Imagine 47-year-old Barack Obama across the stage. McCain loses. Imagine, somehow, that he wins; now imagine the same stage, four years later, with a 76-year-old McCain and a 51-year-old Obama. McCain loses.

Are the optics of McCain's age fatal against any potential Democratic candidate? Not necessarily. With age comes gravitas, or at least the perception thereof. It's no accident that baby-faced John Edwards is considered a light-weight; when you look fifteen years younger than you are, people assume you think fifteen years younger than you are. Unless the American people are desperate for a return to the 90s come 2008, I'd say McCain's age could play well against Edwards. Hillary is more of a tossup, but I think on balance McCain comes out on the losing end of an optics match-up.

But there's more to it than just the optics in '08. There's the need for a reelection campaign at age 76. Reagan's '84 reelection was one of the most masterfully designed and messaged campaigns in modern history. But remember - if McCain is up for reelection in 2012, that will mean that the GOP will have controlled the White House for twelve years. Are GOP voters really prepared to bet the house on a perfect campaign for a septuagenarian four years down the line?

I don't think so. But I don't think the analysis will ever need to get that far. McCain has started his run for the White House, not three days after the mid-term elections. He's the presumptive favorite. He'll be getting an awful lot of media attention. As Michael Ignatieff has discovered, being the early favorite, and garnering all sorts of media attention, can do as much harm as good.

Posted by David Mader at 04:33 PM | (1) | Back to Main

November 09, 2006

It's Official . . .

Starbucks says it's Christmas season:

Posted by David Mader at 08:10 PM | (3) | Back to Main

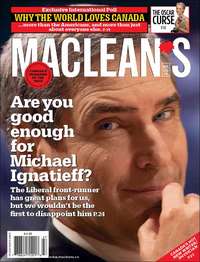

Ouch

The cover of the latest Maclean's:

The text reads: "Are You Good Enough for Michael Ignatieff? The liberal front-runner has great plans for us, but we wouldn't be the first to disappoint him."

Posted by David Mader at 03:16 PM | (0) | Back to Main

November 08, 2006

Clinton in Ottawa

CTV reports:

Former U.S. president Bill Clinton says it would be a mistake to view the results of Tuesday's mid-term elections as a move to the left.Here's more from my mother, who was at the event (these are questions put to Clinton by the organizers; I've paraphrased):Clinton says Americans are demanding a government that is fact-based and doesn't ignore the interests of the middle class and working poor.

He says voters rejected hardheaded ideological politics, where people make up in their mind what the answer is and make the facts fit the answer.

Clinton told an Ottawa fundraiser that the triumph for the Democratic party is clearly a call for a new direction in Iraq.

Asked about North Korea, Clinton criticized what he called an act-alone attitude by the Bush administration. Having called someone evil, he said, you can hardly ask them in for a drink. But, Clinton said, Korea presented less of a challenge than Iran. He suggested that the Korea situation is traceable to the outcome of the Korean War: the Koreans want to be secure but fear U.S. attack and lack the resources to create a self-sufficient country. They resort to militarism in an effort to matter in Asia. Clinton suggested that the US offer aid in modernization and a security guarantee in return for the surrender of the Korean weapons program.There you have it: crack reporting from MaderBlog's maternal correspondent!

Iran, Clinton conceded, was a much more difficult issue. I have a cryptic line from my mother which reads "bush govt should be able to solve it in the next year," but I'm not sure what this means, and I haven't had a chance to speak with her.

Asked about the future of the U.N., Clinton said the organization had to adapt in order to be able to confront 21st century challenges. He said that while the U.N. did a great amount of good (citing Unicef), the organization is institutionally unable, at present, to prevent genocide. He said it is necessary to create a standing U.N. peacekeeping body.

Asked how he would advise Hillary with regard to health care in the event she becomes president, Clinton first noted that Senator Clinton hasn't yet made up her mind to run. He said that in any case she wouldn't need his advice. But he focused on the troubles in the American health care industry, saying that it is wrecking the country and making people miserable. Citing the need to cover all Americans and to reduce administrative costs, Clinton noted improvements in the coverage of working families, but highlighted the growing costs of administration. He noted the rising cost of prescription drugs, the expansion of defensive medicine, and the huge cost of medical malpractice insurance as major concerns. He also highlighted lifestyle issues, including obesity, as well as the inordinate amount of healthcare money spent on the final two months of life.

Finally, Clinton also declared a belief that the U.S. must become more self-sufficient with regard to energy.

Posted by David Mader at 10:23 PM | (0) | Back to Main

Agreeing to Disagree

This seems like a fine example:

WASHINGTON, DC - U.S. Congressman Mike Pence released the following statement today on the GOP's midterm election loss:Nicely put.Election day 2006 will be remembered as a turning point in American political history. Twenty-five years after the Reagan Administration came to Washington with a conservative agenda of limited government, the American people chose a different course.

It is the duty of the losing party in a free election to humbly accept defeat and to acknowledge that the people are sovereign in the People's House.

As we examine the results of this election, it is imperative that we listen to the American people and learn the right lessons.

Some will argue that we lost our majority because of scandals at home and challenges abroad. I say, we did not just lose our majority, we lost our way.

While the scandals of the 109th Congress harmed our cause, the greatest scandal in Washington, D.C. is runaway federal spending.

After 1994, we were a majority committed to balanced federal budgets, entitlement reform and advancing the principles of limited government. In recent years, our majority voted to expand the federal government's role in education, entitlements and pursued spending policies that created record deficits and national debt.

This was not in the Contract with America and Republican voters said, "enough is enough."

Our opponents will say that the American people rejected our Republican vision. I say the American people didn't quit on the Contract with America, we did. And in so doing, we severed the bonds of trust between our party and millions of our most ardent As the 110th Congress convenes next year, Republicans must cordially accept defeat and dedicate ourselves to advancing our cause as the loyal opposition knowing that the only way to retake our natural, governing majority, is to renew our commitment to limited government, national defense, traditional values and reform.

ON THE OTHER HAND: I'm not crazy about this language of "natural, governing majority." Some of the National Review Corner bloggers were griping last night about reports that the Democrats had 'returned' to power. Assuming this is not simply a vestige of the British electoral term 'returns' for 'results,' I wonder whether there isn't something ideological about one's attitudes towards power. In other words, doesn't it make sense that those whose ideology favors an expansive governmental role would consider themselves natural governors, while those whose ideology favors a restricted government role would not? And if so, isn't it natural that third-party observers would develop the same attitude? And if all of that is the case, is it really consistent with the message of Pence's statement to invoke a "natural, governing majority," or might this in fact reflect the very opposite of the message of limited government?

ON THE OTHER OTHER HAND: If you're a small government voter, presumably you'd prefer small-government-minded governors to big-government-minded governors.

Posted by David Mader at 11:43 AM | (0) | Back to Main

Above and Beyond

Well, I predicted that "the press will latch on to the South Dakota [abortion] vote as evidence supporting a general storyline of voter rejection of the GOP," but I must admit I didn't anticipate the audacity with which the press would act. Viz:

In a triple setback for conservatives, South Dakotans rejected a law that would have banned virtually all abortions, Arizona became the first state to defeat an amendment to ban gay marriage and Missouri approved a measure backing stem cell research.That's the lead. If you didn't know better you'd think it had been a bad night for conservative state initiatives. I suppose I shouldn't be that surprised that the press is parroting a particular political attitude; the same head-in-the-sand attitude is evident in this comment on the gay marriage initiatives:

"What we're seeing is that fear-mongering around same-sex marriage is fizzling out," said Matt Foreman, executive director of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force.Fizzling out in the same way that Union military activities fizzled out in the spring of 1865, I should think. Not that I disagree, I suppose, with Foreman's deeper point: that over time anti-gay-marriage attitudes might be expected to fall (although for demographic reasons I'm no longer convinced). But the only way you can spin the initiative results as a setback to conservatives, I think, is to consider particular initiatives in isolation.

ALSO: The article does note one interesting trend that CNN wasn't highlighting last night: nine states approved initiatives restricting the state takings power, a direct response to the Supreme Court's 2005 decision in Kelo v. New London (from which comes the Justice Thomas quotation in the sidebar). Arizona went so far as to require compensation for regulatory takings - which are the diminutions of property value that result from local regulations.

Posted by David Mader at 09:48 AM | (0) | Back to Main

November 07, 2006

Blue Nation?

Andrew Sullivan, predictably, calls tonight's results "a big shift in the minds and souls of Americans." Really? Check out the results in the state-by-state ballot measures. English is now the official language in Arizona. Same sex marriages have been banned (or look to be banned) in seven of eight states considering the question. Slot machines are illegal in Ohio. All three efforts to legalize marijuana have failed. Michigan has banned affirmative action. And at least five of six efforts to raise the state minimum wage have passed - most by a significant margin. (UPDATE: The Times - no, the real Times - reports that the minimum wage initiatives were put on the ballot by Democrats to counter Republican turnout driven by the gay marriage initiatives.)

In other words, party preference aside, Americans appear to have ratified a political agenda that is decidedly socially conservative and fiscally liberal.

In the ideal our neighbors would neither tell us how to live nor spend our money for us. Most of us are probably content to live in a situation in which our neighbors either tell us how to live but don't spend our money for us, or spend our money for us but don't tell us how to live. But the state-by-state results suggest that American "minds and souls" are committed to both spending their neighbors money for them and telling their neighbors how to live.

The irony in all this is that the apparent result - social conservatism coupled with economic liberalism - is precisely the ideological combination that Andrew Sullivan ascribes to the modern Republican Party, and which he says is the antithesis of true conservatism. If he's right, the state-by-state results show not "a big shift in the hearts and minds of Americans" but a comprehensive endorsement of the modern Republican Party ethos.

Think Sullivan will notice?

AS AN ASIDE: Though the Michigan affirmative action law is most easily described as 'conservative,' I'm not sure it's really fairly described as socially conservative, based, as it is, on a formal notion of equality. In fact I'd argue that support for affirmative action is more properly socially conservative, involving as it does the assignment of benefits on the basis of a subjective valuation of racial characteristics. But I may just be saying that because, in the abstract, I think the Michigan law is a good one, and because I don't think of myself as a social conservative. I am, as ever, open to counter-argument.

ALSO: The one big failure of the social conservative movement tonight was the South Dakota abortion ban. (Two initiatives imposing restrictions on abortion - specifically parental notification - are hovering around 50/50, though both appear likely to fail.) I predict that the press will latch on to the South Dakota vote as evidence supporting a general storyline of voter rejection of the GOP. Maderblog readers will, I think, know better.

Posted by David Mader at 11:04 PM | (0) | Back to Main

We Get Results

Ahem:

Posted by David Mader at 05:37 PM | (0) | Back to Main

The Are No Winners

I'm off to my second office/second home to get some reading done, and I probably won't be back until the polls close, so it's time for a prediction.

Regular readers may have noticed that I haven't devoted much attention to the midterm Congressional elections. In fact, this may be my first post directly on the subject. It's not that, from a partisan perspective, I anticipate and disfavor a Democratic victory. It's that, whichever way you cut it, Americans stand to lose.

The Republicans have disappointed, to put it mildly. I believe that the Republic faces an existential threat as great as any it's faced in the past century, perhaps longer. That threat demands a certain gravity and professionalism from our lawmakers. The GOP has singularly failed to live up to the times. Sure, the Congressional party has talked a good talk on the military aspects of the war. But an effort to counter an existential threat must be comprehensive. Republican lawmakers have failed to make the turn from the 1990s to the oughts. From pork-barrel spending to croneyism and the protection of Congressmen from criminal investigation, Congressional Republicans have demonstrated a general failure to transform from a party of the 1990s to a party of the oughts.

But at least they're a party. The Congressional Democratic Party is a joke. The Democrats stand for nothing - nothing except not being Republicans. There are, as I've just noted, many reasons to reject the Republicans. But the Democrats have given no coherent reason why they ought to be preferred. Perhaps Americans could expect greater fiscal restraint from a Democratic Congress - perhaps. But remember that the great 'Democratic' tradition of fiscal restraint in the 1990s - so often touted by Democrats today - resulted from a Democratic White House and a Republican Congress. Nor have the Democrats shown any vision with regard to the war on terror - a war which the party appears institutionally not to believe exists. And despite the media's focus on a Republican culture of corruption, the truth - and all know it - is that Democrat and Republican Congressmen alike suffer from a shameful lack of morals. It's not a partisan thing; it's a fundamental truth about Congress.

Which is why I've been saying, for months, that we should simply cancel the next season of Congress. It started as a joke, but I've come to believe it. It's not practicable, of course; there are budgetary matters that must be attended to. But I'm starting to wonder whether it might be worth letting those matters slide in the service of a general control-alt-delete of national legislative politics.

But today's poll means that there will be yet another season of Congress - the one hundred and tenth - and so it's time to guess at its makeup. I remarked to a buddy today that there's only one result that would actually surprise me: a Republican gain in both chambers. Hardly any other result would seem remarkable at this point: a Republican hold of both chambers; a Republican loss of the House but hold of the Senate; a Republican hold of the House but loss of the Senate; a Democratic gain of both chambers; or a Democratic landslide.

If I had to guess, I'd say that the Dems will take the House by a majority of fewer than five, and that the GOP will hold the Senate by a slimmer margin than they currently enjoy.

Of course, since divided government makes the passage of legislation more difficult; it's not quite shutting the whole place down, but it may be the second best. Don't be fooled, though: Americans still lose.

Posted by David Mader at 04:55 PM | (1) | Back to Main

No Kidding

So there I was at Starbucks, reading my AdminLaw and rocking out my McGill hoodie, when a lady, passing by, leaned in and said, "Did you go to McGill?" Indeed I did, I replied.

"Did you know," she said, "that Zbigniew Brzezinksi went to McGill?"

The fact that I'm not nearly the only McGill alum who would have been as impressed by that fact as I was makes me proud of my alma mater. And yet that little tidbit - true, by the way, insofar as Wikipedia represents the truth - so astounded me that I feel silly not having known it before. Did I? Matt? Stern? Did I know that?

Which brings us to the larger question. What other famous McGill alumnae spring to mind? The only ones I can think of off the top of my head - Shatner, Jan Wong - are a) not that impressive and b) reflective, I think, of an elevation of a particular kind of celebrity cult over a more - how can I say this - nerd-core valuation of noteworthiness. But I have a feeling y'all will know of more famous McGill grads than I do. Suggestions?

UPDATE BEFORE I EVEN POST THIS: It's late, so I'm going to excuse my weak showing on the McGill alum front. I've subsequently cheated, thanks to Wikipedia, and have slapped my head a number of times. (Though I discount those alum who have school buildings named after them.) But don't you cheat; fire away.

Posted by David Mader at 01:44 AM | (6) | Back to Main

November 06, 2006

Just Asking

How come the Government of Canada's handsome and touching new Veterans Week ad - available at the Prime Minister's web page here - isn't up on YouTube? You know, so that web-savvy Canadians could syndicate the ad, for free, on their websites? Seems like a no-brainer to me, but then I don't work in the PMO.

Posted by David Mader at 04:02 PM | (0) | Back to Main

Saddam

Writes The Telegraph:

Saddam was one of the great murderous tyrants of the 20th century; he was a famously evil man. The problem with such characters is that they can take on the reputation of pantomime villains. . . . The truth is that Saddam possessed no more moral scruples than the average serial killer; perhaps fewer, since, unlike the truly psychotic, he was sane. His murders were calculated political acts, and they kept him in power for a scandalously long time. . . .Sic semper.This was not a kangaroo court, and it did not stage a show trial. Given that the responsibility for trying Saddam was – rightly – assigned to his own countrymen, it was unrealistic to expect the legal proceedings to be conducted according to the highest standards. That may sound patronising, but it is a statement of the obvious: as the BBC's John Simpson observed yesterday, "both the defence and the prosecution lawyers had grown up in a legal system which the former Iraqi president himself had controlled". And it is interesting to note that, despite weaknesses in the prosecution case, Saddam – in contrast to Milosevic – forsook effective legal strategies in favour of political grandstanding and patently insincere invocations of the deity.

What the world has witnessed is the end of a trial, conducted in a war zone on behalf of a struggling democracy, in which the defendant was as guilty as sin. The death of Saddam is not a sufficient condition for the establishment of democracy in Iraq, but it is certainly a necessary one.

Posted by David Mader at 01:07 AM | (0) | Back to Main

November 05, 2006

Political Lesson of the Day

When a political campaign calls your news organization and asks you to return materials - a press release, a photo, I dunno, a DVD with ads on it - never, ever, ever give it back.

Posted by David Mader at 11:55 PM | (2) | Back to Main

November 02, 2006

How, Then?

Let's stipulate that Michael Ignatieff doesn't think the proper way to change taxation policy with regard to income trusts is to leak information of the plan to favored investors hours before announcing the policy publicly. How, precisely, does he think such a policy change ought to have been done? He says that "predictability of regulation is more than a virtue in the capital markets," but if that were strictly true there would be no room for a policy change. Is the criticism that the Tory plan doesn't allow enough time for corporations to alter their organizational structure before the new tax rates kick into effect? Or is the criticism that, having said that they wouldn't tax trusts, the Tories would necessarily have introduced "unpredictability" regardless of the specifics of their policy?

Posted by David Mader at 01:13 PM | (1) | Back to Main

Where's My Maclean's?

So the annual university issue is out - but for some odd reason I (a Maclean's subscriber) haven't received a digital copy. It seems to me that not including the university issue in a Maclean's subscription is sort of like not including the swimsuit issue in a Sports Illustrated subscription. A curious business decision, to say the least.

OKAY FINE (17:07): I'm just impatient, apparently. Hooray McGill! Who needs to be the best overall if you're the tops in quality!

Posted by David Mader at 01:08 PM | (6) | Back to Main

Point-Counterpoint II

Another counterpoint provided today by Bjorn Lomborg, who responds to the findings of the recent Stern Review on climate change. Climate change is an area I think requires a substantial degree of empirical knowledge - knowledge that I don't have - so I've refrained from commenting. I do think that between them Stern and Lomborg have focused on the real issue: whether the costs of climate change are greater than the costs required to affect climate change. It might also be worth noting that climate change is perhaps the most extreme example of a field in which proponents of a particular position refuse to disagree.

Posted by David Mader at 12:18 PM | (2) | Back to Main

Point-Counterpoint

Or perhaps point-counterpoint-counter-counterpoint. Yesterday Andrew Coyne responded to Jonathan Kay's mea culpa regarding the Iraq war. Kay, the editorials editor of the National Post, had authored a column confessing his error in supporting the Iraq war. Kay confessed that he had been wrong about the presence of WMD, wrong about the feasibility of fostering democracy in Iraq, and wrong about the decrease in violence that an invasion was expected to bring. (On this last point, note that Kay appeared to lean heavily on a study that has been widely criticized.)

Coyne characterizes Kay as arguing that the Iraq invasion was wrong not just in execution but in principle. I'm not sure that was Kay's point; the column is a bit ambiguous, with language both supporting that proposition ("[the invasion] made the world a more dangerous place overall") and opposing it ("The depressing thing is that it never had to be this way. . . . [T]his war could have had a happy ending (at least from a humanitarian perspective) had Donald Rumsfeld and Paul Wolfowitz listened to the many experts who warned them to put more boots on the ground."). In any case, Coyne argues that to say that the invasion has made the world worse off is to say that the world would be better off if Saddam were still in power; he refutes this suggestion by arguing that while Saddam didn't have WMD at the time of the invasion he had plans to reacquire them as soon as the international pressure on him was removed.

Almost as if in response, Boris Johnson argues in today's Telegraph that in fact the Iraq campaign was doomed from the get go.

It is now commonplace for people like me, who supported the war, to say that we "did the right thing" but that it had mysteriously "turned out wrong". This is intellectually vacuous. It is like saying British strategy for July 1, 1916 was perfect, but let down by faulty execution. The thing was a disaster from the moment we invaded, and it wasn't poor old Rumsfeld's fault for failing to send in enough troops, or failing to do more "planning" for the post-war. No quantity of troops could have prevented this catastrophe.This, to me, is the most powerful criticism of support for the war. I'm tempted to say it's typical that it comes from a conservative. As Johnson argues, the actual prosecution of the war effort has no impact on the ultimate wisdom of the war if, and only if, the war was doomed from the get-go.

Like Coyne I'm not prepared to confess error in my support for the Iraq war, though unlike Coyne my rationale isn't (and has never predominantly been) about WMD. Here's an argument I made in the comments to this post:

The neocon argument in support of the Iraq war goes (basically) something like this: radical Islamism poses a existential threat to the democratic west. The threat is at once philosophical and military: Islamism (as used here) is an ideology that denies and rejects certain fundaments of western democracy, and which supports and encourages actual measures - including the use of force - to undermine western democracy and replace it with a system of governance more conducive to the Islamist interpretation of Islam. The conflict with Islamism therefore has a primary ideological and a secondary military component. If the ideological battle can be won, prolongued military conflict can be avoided. Victort in the ideological battle requires something of a reformation in Islam in order to make Islamism (as herein used) unpalatable to mainstream Muslims.Johnson's argument suggests that - regardless of motivation - the invasion of Iraq was doomed to failure. I'm not convinced that's true. At the very least I think there was an outside chance of success - and, given the stakes, I think that even an outside chance was worth it. That being the case, I think I'm justified in adhering to the Kay line of "it didn't have to turn out like this."Here's the neocon leap: the key to winning the ideological battle is democratization. Tyranny breeds the sort of disdain for human rights that feeds Islamism. Democratization both inculcates a sense of respect for individual liberties and provides an outlet for frustrations that might otherwise be expressed through Islamist activity.

That being the case, the challenge is to introduce democracy into the Arab Muslim world. [It's true] that there were many candidate countries that were both tyrannical and breeding grounds for Islamism. Indeed, most of the Arab middle east is tyrannical to a greater or lesser extent. The question is, of all the tyrannies in the Arab middle east, which was - in the period 2002/03 - the most egregious tyranny and (in part therefore) the most likely to serve as an example to the surrounding nations? And there's at least a colorable argument to be made that Iraq was the one country that fit the bill. Saddam was the poster-boy of Arab anti-Americanism; given Iraq's prominence (both political and geographical) in the middle east, the fomentation of a functioning democracy there would (the argument went) stand as good a chance as any to seed democracy in the region.

[N]ote that it's immaterial whether or not Saddam himself was an Islamist; what matters is whether his continued rule would contribute to the general regional tyranny that serves as the foundation for Islamist ideology and activity.

But let me turn the tables on Johnson by posing a counter-question: assuming a) that the invasion of Iraq had - or has - something to do with radical Islamist violence, including such violence in the UK, and b) that the invasion has failed, what is the proper next step in the UK's confrontation of radical Islamism? In short, what now?

Posted by David Mader at 10:33 AM | (3) | Back to Main

November 01, 2006

Where's Wells?

You know, if I were Paul Wells, and my popular blog went down the day before the launch of my first book, I'd be pretty annoyed.

Just saying.

Posted by David Mader at 10:09 PM | (0) | Back to Main

Promises, Promises

I think I generally agree with Coyne's take on the income trust thing; that is, I think the change in tax treatment was probably necessary and inevitable, but I think the Tories have exposed themselves to a fair degree of criticism for an apparently patent about-face. This about-face is all the more dangerous, I think, because one of the Tory government's most popular characteristics has been the fact that it's done what it said it would do. (Still, better to break a promise on a policy with which few can really disagree.)

But I can't join in Coyne's call for a legal remedy against politicians who break promises. Campaign promises—and the policies they involve—are the very definition of 'political questions' which the courts are ill-suited to address. I understand that Canadian politicos are less wound-up about Montesquieu's separation of powers, but there are good reasons to keep political questions away from the judiciary.

How would judges determine whether a politician had broken a campaign promise? It sounds easy in practice—"you promised not to raise taxes, and you raised taxes"—but even the most general example is subject to debate. If a new government cancels a planned tax cut, has it raised taxes? It's raised taxes relative to an alternative, true, but an alternative that never came to pass. I should think that how you view the cancellation of a planned but never executed alternative policy will have much to do with political ideology. What standard would a court use to determine breach in such a case—what standard, that is, other than political ideology?

Moreover, subjecting campaign promises to judicial oversight threatens, I think, to chill constructive legislative activity, including compromise—or to chill campaigning. On the one hand, a candidate might make an entirely good-faith pledge on the stump, only to find that compromise on that particular policy is necessary to achieve constructive legislative action on another policy plank. Is it really a good idea to subject this sort of compromise to legal liability? On the other hand, competing candidates might become unwilling to make anything but the blandest statements while on the stump, leaving voters with no real notion of what they would do if elected—or how they differ from one another in terms of ideology or policy preference. Is it really a good idea to discourage ideological identification in our elections?

I understand Coyne's frustration, I think. But precisely because campaign promises are broken in the service of explicitly political activity, those promises are manifestly unfit for judicial review—and manifestly fit for political review at the next election.

If Coyne wants more of a check, how about more frequent elections? In fact one could argue that the current pattern of general elections once every other year has resulted in the most dynamic political environment, from a policy standpoint, in recent memory.

Posted by David Mader at 09:40 PM | (2) | Back to Main

Societal Impact of Same Sex Marriage

A while back I noted the argument by ethicist Margaret Somerville that we have not (and perhaps cannot) anticipate the effects that the recognition of same sex marriage will have on our society. Now Volokh Conspirator Dale Carpenter relays some data:

Seventeen years after recognizing same-sex relationships in Scandinavia there are higher marriage rates for heterosexuals, lower divorce rates, lower rates for out-of-wedlock births, lower STD rates, more stable and durable gay relationships, more monogamy among gay couples, and so far no slippery slope to polygamy, incestuous marriages, or "man-on-dog" unions.As I've previously argued, the mere possibility of adverse societal consequences should not, I think, be enough to prevent a recognition of same sex marriage (if such a recognition is otherwise desirable); it's interesting, in any case, to see data that appears to contradict (to a greater or lesser degree) the 'societal risk' theory of opposition to SSM.

Posted by David Mader at 07:12 PM | (2) | Back to Main

Quote of the Day

From Lileks:

Luck is like Communism – believe in it if you like, just don’t base your actions on it.Runner up, from the same source:

Auto racing on the radio would be like golf described via semaphore flags, but some people like it.Read the whole thing, particularly if you're a semi-regular Lileks reader; he's definitely on form.

I agree with him about Kerry, incidentally. I do think the guy meant to be making a joke about Bush. I just think that his failure to anticipate how it would come across, combined with his utter failure to manage the gaffe, demonstrate, shall we say, the full scope of his political acumen. At this point he might as well just retire.

Posted by David Mader at 12:51 AM | (1) | Back to Main

On Disagreement

Here's an unfortunate though unsurprising story from the New York Times:

For years, Sheri Langham looked at the Republican politics of her parents as a tolerable quirk, one she could roll her eyes at and turn away from when the disagreements grew a bit deep.The article suggests that we may be moving back towards a social more that holds it impolite to talk politics in company. I think that misses the point, and I think the point is this: we, as a society, have increasingly forgotten how to disagree.But earlier this year, Ms. Langham, 37, an ardent Democrat, found herself suddenly unable even to speak to her 65-year-old mother, a retiree in Arizona who, as an enthusiastic supporter of President Bush, “became the face of the enemy,” she said.

“Things were getting to me, and it became such a moral litmus test that all I could think about was, ‘How can she support these people?’ ” said Ms. Langham, a stay-at-home mother in suburban Virginia.

The mother and daughter had been close, but suddenly they stopped talking and exchanging e-mail messages. The freeze lasted almost a month. . . .

Bob Schwartz, a Democrat in Columbus, has had a similar, visceral reaction to his Republican friends. He recently quit his monthly poker game after 25 years, he had become so fed up with hearing his Republican partners praise President Bush at every gathering.

“It finally got to the point where it was me and another guy who were the only Democrats in there, and we said ‘That’s it, folks, we don’t want to play anymore,’ ” said Mr. Schwartz, 68, who is a retired electrical contractor. . . .

Jim Coffman, 40, a Democrat in Chicago, said he and his wife have not pursued a friendship with another couple whose three children are the same ages as theirs after seeing photographs of President Bush on the other couple’s refrigerator. He said they have discussed with other friends “being so amazed that we could have so much in common, and yet be so diametrically opposed” when it comes to politics.

Which is not to say that we don't disagree, of course. What we've forgotten is that it's okay to disagree, that indeed it's healthy, and probably necessary, to disagree, and that disagreement doesn't have to turn opponents in a disagreement into enemies.

This is a subject that fascinates me, actually, and I'm developing my own sort of theory of disagreement. I won't bore you all with it - it's something I poke around with periodically - but I'll outline my thinking on the core issue of disagreement.

As I see it the current failure to disagree is manifest in two different ways. At the most extreme, the failure stems from a combination of moral conviction and intellectual incuriosity. By moral conviction I mean a conviction based upon a normative preference for a particular first-principle value. Moral conviction is a fine thing, of course, but only to the extent that it is subject to criticism. To paraphrase Milton, I cannot praise a fugitive and cloistered moral. Precisely because a moral conviction is based upon a belief as to a first principle, it's important that the conviction be subject to criticism in order for the holder of the conviction to determine whether that conviction is (or ought to be) truly held. Normative choices are by definition beyond falsification, but that makes it all the more important, I think, to reduce the normative element by subjecting the consequences of a normative preference to rational criticism.

This unwillingness to subject one's moral convictions to criticism I term a lack of intellectual curiosity. This has nothing to do with intelligence; the most intelligent person can be unwilling to expose his or her moral convictions to criticism. But whether intelligent or ignorant, the individual who refuses to subject his or her moral convictions to challenge fundamentally refuses to engage in reasoned debate, and so refuses to disagree. "You’re wrong" is no argument.

More common and less extreme than the refusal to engage is what I call the stupid/evil paradox. This comes into play when a party to an argument acknowledges the contrary position but assumes that the party proposing it would not be if he or she weren’t stupid or evil. The assumption is rarely voiced in these terms, but it exists. Appeals to personal experience or (in certain circumstances) to statistics are often signs of an assumption of stupidity. An assumption of stupidity grants the contrary party a benign intent but presupposes that with more information or understanding the contrarian would abandon his or her position. In other words, the stupidity assumption denies that an intelligent person could hold the contrary view.

The assumption of evil intent is essentially the inverse of the assumption of stupidity. It credits the contrarian with intelligence but presupposes malice. Accusations of heartlessness or prejudice are often signs of an assumption of evil. The party assuming evil recognizes the intellectual force of the contrary position but denies that it can be held by anyone who is kind, or just, or who otherwise lacks malice.

The paradox exists in the fact that an opponent is credited either with benign intent or with intelligence but never with both. As a result, those who fall into the stupid/evil paradox are only marginally more successful at arriving at actual disagreement than are those who refuse to engage altogether. While they superficially acknowledge the contrary position, their assumptions make them fundamentally incapable of actually confronting them. Those without intellectual curiosity fail to acknowledge contrary positions; those governed by the stupid/evil paradox fail to understand them.

Overcoming the stupid/evil paradox is the most important step towards proper disagreement. (It is also, incidentally, an integral step to agreement as well.) Only once one has credited one’s opponent with both intelligence and a non-malicious intent will one turn to the merits of his or her argument. One may well find—probably will find—certain assumptions or moral convictions underlying the contrary position which one does not share. The identification of such underlying convictions—I would call them first principles—often marks the successful completion of a debate or argument; after all, to the degree that first principles reflect normative choices, there will likely be little room for rational debate as to the particular normative choice that ought to be preferred. One party may, however, realize that he or she has in fact been arguing a position that is revealed to be inconsistent with a first principle which he or she in the abstract prefers, and may in fact change his or her mind—leading to agreement, rather than disagreement. Obviously, this is impossible to those who are intellectually incurious or who assume stupidity or malice.

Even if the revelation of underlying first principles does not lead to agreement, however, it will lead to something equally valuable: true disagreement. Parties to a discussion that results in the discovery of underlying first principles will come away with an understanding that intelligent, honest people can hold a view contrary to their own, and—perhaps more importantly—they will come away with an understanding of the assumptions, the first principles, that result in the contrary position. The first understanding will result in civility, and perhaps proper respect. The second understanding can lead to conciliation. While first principles tend to be broad—take a preference for liberty over equality at the margin—they can, perhaps paradoxically, be narrower than the universe of principles that might otherwise appear to attach to the position that has been built upon the first principle. If the first principle is the point of contention—as it inevitably must be—it remains true that two contrary first principles will not be made to overlap; but it’s entirely possible that enough of the peripheral principles will be found non-essential to adherence to the first principle to allow a certain amount of overlap. In other words—and in plain English—determining first principles will reveal possible areas of common ground.

Obviously a work in progress; thoughts, comments, questions are all welcome. (And yes, I understand perfectly well how pretentious it all sounds. That's the nature of philosophizing, I think.) (And no, I don't claim to be innocent of the mistakes I highlight - not at all. I'm just describing them.)

Posted by David Mader at 12:08 AM | (5) | Back to Main